The aviation blogosphere is a fairly small place, and the closest thing it has to an organization is a Pilotbloggers email list I subscribe to. A bunch of the other members are participating in a mass post today regarding New Year's Resolutions. Well, I don't normally do New Year's Resolutions - I moreso have a master list of long-term goals that get updated occasionally. But I haven't been a very good member of the aviation blogosphere lately - little reading, less linking - so I feel I should post something today.

My initial thought for a resolution is to remain employed as a pilot by the end of 2009. That's not really a good goal, though - there are too many factors outside my control. So that's more of a hope and a prayer than a resolution.

So my official resolution to finish the book by the end of the year. Not published, just finished.

Sunday, December 28, 2008

Saturday, December 27, 2008

About That Pilot Shortage...

Since even before I started flying in 1994, I've been hearing about an ever-looming severe pilot shortage. This is a theory that has been promoted most vigorously and infamously by Kit Darby of Air, Inc, but has been repeated at length by various aviation publications and eagerly endorsed by the flight training industry. The idea is that a large contingent of Vietnam-era airline pilots are approaching retirement age at the same time that industry growth creates a need for additional pilots, and not enough new pilots are being trained to fill both needs. The effects will be intense, widespread, and will have far-reaching implications for the airline industry, say the proponents of this theory.

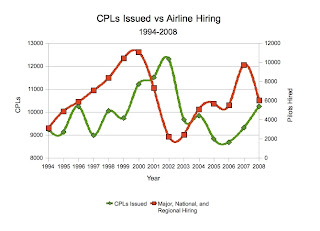

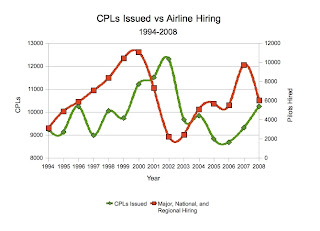

I've seen two large booms in airline pilot hiring in the last 14 years which were, at the time, thought to be the onset of the predicted pilot shortage. Graph 1 below tells the story of boom and bust; it is based on hiring data published by Air, Inc, which despite a minor conflict of interest between collecting/publishing hiring data and selling interview prep materials to aspiring airline pilots remains the industry's most authoritative source of hiring data.

After war, terrorism, and economic turmoil led to the shutdown of Eastern and PanAm and the furlough of thousands of pilots at the other major airlines in the early 90s, steady economic growth paved the way for the airlines' comeback in the middle and later parts of that decade. By 1995 most furloughees had been recalled and major airline hiring increased steadily from 1200 pilots in 1994 to 5000 pilots in 1999. From 1997 to 2000, hiring at national and regional airlines ($100M to $1B in annual revenue) outpaced hiring at the majors, largely driven by the advent of 30-50 seat jets at the regional airlines. 2000 was the height of the hiring boom. Although major airline hiring had eased somewhat, the regionals and nationals more than made up the difference and pushed airline hiring to an all-time high of over 11000 pilots. At the time it looked like the onset of a major shortage. Retirements were just starting to increase and the majors were forecast to grow significantly in the next decade; the regionals frenetically hired pilots to replace those who moved on to the majors, and many were hiring pilots with as little as 500 to 1000 hours. Flight schools had a horrible time keeping instructors around; as soon as they accumulated a few hundred hours, they were off to the airlines. It seemed like a very good time to have one's foot in the door of the aviation industry.

After war, terrorism, and economic turmoil led to the shutdown of Eastern and PanAm and the furlough of thousands of pilots at the other major airlines in the early 90s, steady economic growth paved the way for the airlines' comeback in the middle and later parts of that decade. By 1995 most furloughees had been recalled and major airline hiring increased steadily from 1200 pilots in 1994 to 5000 pilots in 1999. From 1997 to 2000, hiring at national and regional airlines ($100M to $1B in annual revenue) outpaced hiring at the majors, largely driven by the advent of 30-50 seat jets at the regional airlines. 2000 was the height of the hiring boom. Although major airline hiring had eased somewhat, the regionals and nationals more than made up the difference and pushed airline hiring to an all-time high of over 11000 pilots. At the time it looked like the onset of a major shortage. Retirements were just starting to increase and the majors were forecast to grow significantly in the next decade; the regionals frenetically hired pilots to replace those who moved on to the majors, and many were hiring pilots with as little as 500 to 1000 hours. Flight schools had a horrible time keeping instructors around; as soon as they accumulated a few hundred hours, they were off to the airlines. It seemed like a very good time to have one's foot in the door of the aviation industry.

Even if 9/11 hadn't happened, it's likely that the collapse of the dot com bubble economy would've still devastated the airlines. The planes were fairly full within a few months of the attacks; the expense-account business travelers, however, did not come back (or rather, modified their travel purchasing habits), a trend that had already begun in early 2001. The major airlines had built their business models around these travelers in the 90s, and their disappearance devastated the industry. In this difficult, uncertain environment, the major airlines made significant cuts to their flying, which resulted in many thousands of furloughed pilots and the total collapse of hiring between 2000 and 2003. Hiring minimums at the few airlines still recruiting shot skyward.

The second major boom took place only last year. The data in the years leading up to it is more confused than it was in the 90s and requires some explanation. The majors' hiring trended upward after 2003 and was back at moderate levels by 2005. This was driven entirely by the growth of low-cost carriers like Southwest, AirTran, and jetBlue, and freight carriers FedEx and UPS. The "legacy" airlines had no hiring; in 2005, four of the six were simultaneously in bankruptcy and all still had thousands of furloughees on the street. The expanding low-cost and freight carriers hired largely from this pool of furloughees. The regionals and nationals saw fairly low attrition during this time; the large hiring bump from 2002 to 2004 was due to growth thanks to the relaxation of scope in the major airline pilots' post-9/11 concessionary contracts. As these new air regional hiring leveled off in 2005 and 2006.

In 2007 the dynamic changed. By the end of 2006, all the legacies were out of bankruptcy with drastically altered cost structures, and the low cost carriers' growth slowed. Most of the legacies' remaining furloughees were recalled, and by mid 2007 most of the legacies were hiring again for the first time in six years. This time, the majority of civilian newhires came from the regional carriers, and attrition there skyrocketed. This happened at the same time that many regionals were expanding due to the delivery of 70-86 seat jets that were allowed to be outsourced by contracts imposed in the majors' bankruptcies. The result was that the national and regional airlines' hiring doubled between 2006 and 2007, and they suffered a pilot shortage more acute than 2000-2001. The regionals couldn't find enough pilots to fill their classes; hiring minimums fell to the bare legal minimum for the first time in 40 years and handsome signing bonuses were offered to applicants with prior airline experience. There were discussions within the industry that the lack of qualified pilots posed a threat to some regionals' very survival, particularly those with high attrition. This rather acute shortage ended abruptly in the spring of 2008 as high fuel prices brought a halt to hiring at the majors and made the 30-50 seat RJs horrifically costly to operate on a per-seat basis. When fuel prices eased in the latter part of 2008, it was in response to a collapsing economy that posed an equal threat to the airlines; thousands of pilots are again on the street, this time at both majors and regionals. At the same time, retirements are way down thanks to a recent increase in the mandatory retirement age from 60 to 65. Hiring prospects for 2009 look bleak.

With so many surplus pilots during two periods of a single decade, it's easy to dismiss talk of a pilot shortage as nothing but snake oil peddled by the flight training industry, and many pilots do think it was nothing more than the brainchild of Kit Darby. I think it depends on how you define a shortage. The hiring booms clearly had some of the makings of a shortage; neither bubble, however, constituted a truly acute, industry-wide shortage as had been predicted. The boom of 1994-2000 was widespread and prolonged, but was never any sort of threat to the industry. Hiring minimums decreased at both majors and regionals, but neither had much trouble finding qualified candidates. In 2007, the shortage was very acute but limited strictly to the regional airlines; the majors had a huge pool of qualified, motivated candidates to choose from. I believe that these two scenarios are as close to a pilot shortage as we will ever come in the United States. I also believe that the second type of pilot shortage will return with a vengeance several years from now.

My reasoning is based on the supply of new pilots and how it fluctuates in response to varying hiring markets. There isn't any available data on how many people begin flight training each year with a goal of flying for the airlines, but we do know how many commercial pilot licenses the FAA issues every year. Clearly not everyone who is issued a CPL intends to fly for the airlines or even fly professionally, but given that every would-be professional pilot must first earn a CPL it seems reasonable to use this as a gauge of the supply of pilots entering the industry. Refer to Graph 2 below, which charts annual CPL issuances against total airline hiring.

One can see that there is a fairly strong correlation between the strength of the hiring market and the number of CPL issuances. There is also a pronounced 2-3 year lag between the peaks and valleys of hiring and those of CPL issuances. Both conclusions make sense: obviously people find it most worthwhile to invest time and money into flight training when the aviation industry is doing well, and it may be several years between that decision to enter aviation and earning one's CPL. By comparison, the number of Airline Transport Pilot (ATP) certificates issued tracks very closely to the strength of the hiring market with little lag (see Graph 3 below). Once one has the required flight time for an ATP, the training is quite short compared to the CPL. So from these two charts, it is obvious that both pilots and potential pilots take the strength of the hiring market into strong account when deciding whether to invest in training, but the actual supply of new commercial pilots is affected only several years later when the hiring market may be entirely different.

One can see that there is a fairly strong correlation between the strength of the hiring market and the number of CPL issuances. There is also a pronounced 2-3 year lag between the peaks and valleys of hiring and those of CPL issuances. Both conclusions make sense: obviously people find it most worthwhile to invest time and money into flight training when the aviation industry is doing well, and it may be several years between that decision to enter aviation and earning one's CPL. By comparison, the number of Airline Transport Pilot (ATP) certificates issued tracks very closely to the strength of the hiring market with little lag (see Graph 3 below). Once one has the required flight time for an ATP, the training is quite short compared to the CPL. So from these two charts, it is obvious that both pilots and potential pilots take the strength of the hiring market into strong account when deciding whether to invest in training, but the actual supply of new commercial pilots is affected only several years later when the hiring market may be entirely different. By the time the first hiring boom reached its peak in 2000, hiring had been increasing very steadily for six years. Accordingly, the number of CPLs issued had increased since 1997, and there was a rather steady supply of new pilots that prevented the boom from ever becoming a severe shortage. Even if 9/11 and the dot com implosion never happened, I suspect that flight training could've easily kept up with airline growth and retirements. There is a lot of flight training infrastructure in this country that can be utilized when times are good and people choose to invest in flight training (incidentally, the lack of such infrastructure is why the pilot shortage is very real in overseas emerging markets). I seriously doubt that any extended period of growth and retirements will translate into a severe, prolonged pilot shortage.

By the time the first hiring boom reached its peak in 2000, hiring had been increasing very steadily for six years. Accordingly, the number of CPLs issued had increased since 1997, and there was a rather steady supply of new pilots that prevented the boom from ever becoming a severe shortage. Even if 9/11 and the dot com implosion never happened, I suspect that flight training could've easily kept up with airline growth and retirements. There is a lot of flight training infrastructure in this country that can be utilized when times are good and people choose to invest in flight training (incidentally, the lack of such infrastructure is why the pilot shortage is very real in overseas emerging markets). I seriously doubt that any extended period of growth and retirements will translate into a severe, prolonged pilot shortage.

The boom of 2007 was different. Although airline hiring had increased between 2002 and 2006, it was not the sort of steady growth across all sectors that characterized 1994-2000, and it was a period of instability for the airlines. The woes of the legacies and the plights of their pilots - contracts gutted and pensions terminated in bankruptcy - were very much in the news. These are not the conditions that inspire people to sign up for flight training. Accordingly, CPL issuances reached their post-9/11 nadir in 2006 and posted only a modest gain in 2007. When the regional airlines suddenly had to hire 6800 pilots in 2007 - double that of 2006 and 235% more than Air, Inc had predicted at the beginning of the year - several years of depressed training translated into a dearth of qualified pilots. Hiring minimums plummeted, and those airlines with the highest attrition (i.e., most pilot-unfriendly management) were forced to hire pilots with the minimum legal qualifications - and they still couldn't find enough pilots. If this hiring environment had continued - if high oil prices and the economy hadn't killed of the demand for pilots - it is likely that CPL issuances would've continued the upswing seen in 2007-2008 and eventually satisfied the industry's demand for pilots. In the meantime, though, the shortage would've posed a distinct challenge for the airline industry and a distinct opportunity for pilots.

So what does the future hold? I think 2009 is going to be a very rough year for airline pilots. Although oil prices have fallen significantly, it's anybody's guess as to when and where the economy will bottom out and begin its recovery. All the airlines are forecasting significantly decreased revenue for next year; many forecasts have revenue falling more than in 1987, 1991, or 2001-2002. Accordingly, the airlines have made significant capacity cuts with more probably on the way. To the airlines' advantage, the credit crunch should ensure there are no upstarts to play spoiler by increasing overall capacity like in 2001-2006, but this also means there will likely be no hiring at low cost carriers to absorb the legacies' furloughees. Many regional airlines, too, are facing contraction as their major airline partners try to reduce their exposure to 30-50 seat RJs. Meanwhile, the change to the retirement age means retirements will be significantly below normal until 2012. My guess is that overall hiring for 2009 will be significantly lower than 2002, with a depressed job market for several years after that.

Eventually, though, the shortage at the regionals we saw in 2007 will return, and it will be worse next time. Although CPL issuances will continue to rise for another one or two years, after that you'll see a sharp drop like that in 2003. I think the training slump will be much lower than it was in 2003-2006. Back then, there were still jobs available at the regionals even if the majors were still in turmoil; this time there will be few airline jobs of any description for several years straight. The cost of flight training has increased significantly in the last few years. It will also be harder to secure loans for flight training as long as the credit crunch endures. During the next few years, there will be a lot of people stuck flight instructing, flying freight, etc, but this surplus will only obscure the fact that there are fewer and fewer new pilots being trained.

When the economy begins its recovery and the airlines start adding capacity back into their systems - several years from now, I'm guessing - they will initially have no problem finding qualified candidates for their openings. The majors, of course, will hire from the huge cadre of regional airline captains chomping at the bit to move up to the next level, and the regionals will be able to draw from the pool of flight instructors and freight dogs that formed during the years without airline hiring. If the hiring ramped up slowly and steadily, I would expect the training of new pilots to increase enough by the time this pool is depleted that the boom would never become a shortage. There is a complicating factor, though: the first wave of airline pilots to hit age 65 will retire in 2012 and double or even triple the annual number of retirements. If this happens concurrently with an industry growth period, attrition at the regionals will skyrocket and quickly deplete the pool of experienced pilots. I think you'll see a very similar shortage to 2007, but without several years of preceding hiring activity like 2004-2006 to stimulate new training. You'll see a return of 250 hour commercial pilots to the right seat of airliners (or even less qualified, if the ATA gets it's way on Multi-Pilot License). You'll also see a return of signing bonuses for experienced pilots. This situation will persist for several years until the people it lures into aviation complete their training. It will be a unique opportunity for regional pilots to get better contracts without fear that their flying will be replaced by a lower-cost regional.

In the meantime, those of us at the regionals aren't going anywhere - if we're lucky. I personally don't have a great deal of faith that I'll be employed at NewCo this time next year, in the left seat anyways. If that happens, there's a good chance I'll be heading overseas - where the pilot shortage is very real indeed and still ongoing, and a pilots' services are therefore valued more highly than in the erstwhile "land of opportunity".

I've seen two large booms in airline pilot hiring in the last 14 years which were, at the time, thought to be the onset of the predicted pilot shortage. Graph 1 below tells the story of boom and bust; it is based on hiring data published by Air, Inc, which despite a minor conflict of interest between collecting/publishing hiring data and selling interview prep materials to aspiring airline pilots remains the industry's most authoritative source of hiring data.

After war, terrorism, and economic turmoil led to the shutdown of Eastern and PanAm and the furlough of thousands of pilots at the other major airlines in the early 90s, steady economic growth paved the way for the airlines' comeback in the middle and later parts of that decade. By 1995 most furloughees had been recalled and major airline hiring increased steadily from 1200 pilots in 1994 to 5000 pilots in 1999. From 1997 to 2000, hiring at national and regional airlines ($100M to $1B in annual revenue) outpaced hiring at the majors, largely driven by the advent of 30-50 seat jets at the regional airlines. 2000 was the height of the hiring boom. Although major airline hiring had eased somewhat, the regionals and nationals more than made up the difference and pushed airline hiring to an all-time high of over 11000 pilots. At the time it looked like the onset of a major shortage. Retirements were just starting to increase and the majors were forecast to grow significantly in the next decade; the regionals frenetically hired pilots to replace those who moved on to the majors, and many were hiring pilots with as little as 500 to 1000 hours. Flight schools had a horrible time keeping instructors around; as soon as they accumulated a few hundred hours, they were off to the airlines. It seemed like a very good time to have one's foot in the door of the aviation industry.

After war, terrorism, and economic turmoil led to the shutdown of Eastern and PanAm and the furlough of thousands of pilots at the other major airlines in the early 90s, steady economic growth paved the way for the airlines' comeback in the middle and later parts of that decade. By 1995 most furloughees had been recalled and major airline hiring increased steadily from 1200 pilots in 1994 to 5000 pilots in 1999. From 1997 to 2000, hiring at national and regional airlines ($100M to $1B in annual revenue) outpaced hiring at the majors, largely driven by the advent of 30-50 seat jets at the regional airlines. 2000 was the height of the hiring boom. Although major airline hiring had eased somewhat, the regionals and nationals more than made up the difference and pushed airline hiring to an all-time high of over 11000 pilots. At the time it looked like the onset of a major shortage. Retirements were just starting to increase and the majors were forecast to grow significantly in the next decade; the regionals frenetically hired pilots to replace those who moved on to the majors, and many were hiring pilots with as little as 500 to 1000 hours. Flight schools had a horrible time keeping instructors around; as soon as they accumulated a few hundred hours, they were off to the airlines. It seemed like a very good time to have one's foot in the door of the aviation industry.Even if 9/11 hadn't happened, it's likely that the collapse of the dot com bubble economy would've still devastated the airlines. The planes were fairly full within a few months of the attacks; the expense-account business travelers, however, did not come back (or rather, modified their travel purchasing habits), a trend that had already begun in early 2001. The major airlines had built their business models around these travelers in the 90s, and their disappearance devastated the industry. In this difficult, uncertain environment, the major airlines made significant cuts to their flying, which resulted in many thousands of furloughed pilots and the total collapse of hiring between 2000 and 2003. Hiring minimums at the few airlines still recruiting shot skyward.

The second major boom took place only last year. The data in the years leading up to it is more confused than it was in the 90s and requires some explanation. The majors' hiring trended upward after 2003 and was back at moderate levels by 2005. This was driven entirely by the growth of low-cost carriers like Southwest, AirTran, and jetBlue, and freight carriers FedEx and UPS. The "legacy" airlines had no hiring; in 2005, four of the six were simultaneously in bankruptcy and all still had thousands of furloughees on the street. The expanding low-cost and freight carriers hired largely from this pool of furloughees. The regionals and nationals saw fairly low attrition during this time; the large hiring bump from 2002 to 2004 was due to growth thanks to the relaxation of scope in the major airline pilots' post-9/11 concessionary contracts. As these new air regional hiring leveled off in 2005 and 2006.

In 2007 the dynamic changed. By the end of 2006, all the legacies were out of bankruptcy with drastically altered cost structures, and the low cost carriers' growth slowed. Most of the legacies' remaining furloughees were recalled, and by mid 2007 most of the legacies were hiring again for the first time in six years. This time, the majority of civilian newhires came from the regional carriers, and attrition there skyrocketed. This happened at the same time that many regionals were expanding due to the delivery of 70-86 seat jets that were allowed to be outsourced by contracts imposed in the majors' bankruptcies. The result was that the national and regional airlines' hiring doubled between 2006 and 2007, and they suffered a pilot shortage more acute than 2000-2001. The regionals couldn't find enough pilots to fill their classes; hiring minimums fell to the bare legal minimum for the first time in 40 years and handsome signing bonuses were offered to applicants with prior airline experience. There were discussions within the industry that the lack of qualified pilots posed a threat to some regionals' very survival, particularly those with high attrition. This rather acute shortage ended abruptly in the spring of 2008 as high fuel prices brought a halt to hiring at the majors and made the 30-50 seat RJs horrifically costly to operate on a per-seat basis. When fuel prices eased in the latter part of 2008, it was in response to a collapsing economy that posed an equal threat to the airlines; thousands of pilots are again on the street, this time at both majors and regionals. At the same time, retirements are way down thanks to a recent increase in the mandatory retirement age from 60 to 65. Hiring prospects for 2009 look bleak.

With so many surplus pilots during two periods of a single decade, it's easy to dismiss talk of a pilot shortage as nothing but snake oil peddled by the flight training industry, and many pilots do think it was nothing more than the brainchild of Kit Darby. I think it depends on how you define a shortage. The hiring booms clearly had some of the makings of a shortage; neither bubble, however, constituted a truly acute, industry-wide shortage as had been predicted. The boom of 1994-2000 was widespread and prolonged, but was never any sort of threat to the industry. Hiring minimums decreased at both majors and regionals, but neither had much trouble finding qualified candidates. In 2007, the shortage was very acute but limited strictly to the regional airlines; the majors had a huge pool of qualified, motivated candidates to choose from. I believe that these two scenarios are as close to a pilot shortage as we will ever come in the United States. I also believe that the second type of pilot shortage will return with a vengeance several years from now.

My reasoning is based on the supply of new pilots and how it fluctuates in response to varying hiring markets. There isn't any available data on how many people begin flight training each year with a goal of flying for the airlines, but we do know how many commercial pilot licenses the FAA issues every year. Clearly not everyone who is issued a CPL intends to fly for the airlines or even fly professionally, but given that every would-be professional pilot must first earn a CPL it seems reasonable to use this as a gauge of the supply of pilots entering the industry. Refer to Graph 2 below, which charts annual CPL issuances against total airline hiring.

One can see that there is a fairly strong correlation between the strength of the hiring market and the number of CPL issuances. There is also a pronounced 2-3 year lag between the peaks and valleys of hiring and those of CPL issuances. Both conclusions make sense: obviously people find it most worthwhile to invest time and money into flight training when the aviation industry is doing well, and it may be several years between that decision to enter aviation and earning one's CPL. By comparison, the number of Airline Transport Pilot (ATP) certificates issued tracks very closely to the strength of the hiring market with little lag (see Graph 3 below). Once one has the required flight time for an ATP, the training is quite short compared to the CPL. So from these two charts, it is obvious that both pilots and potential pilots take the strength of the hiring market into strong account when deciding whether to invest in training, but the actual supply of new commercial pilots is affected only several years later when the hiring market may be entirely different.

One can see that there is a fairly strong correlation between the strength of the hiring market and the number of CPL issuances. There is also a pronounced 2-3 year lag between the peaks and valleys of hiring and those of CPL issuances. Both conclusions make sense: obviously people find it most worthwhile to invest time and money into flight training when the aviation industry is doing well, and it may be several years between that decision to enter aviation and earning one's CPL. By comparison, the number of Airline Transport Pilot (ATP) certificates issued tracks very closely to the strength of the hiring market with little lag (see Graph 3 below). Once one has the required flight time for an ATP, the training is quite short compared to the CPL. So from these two charts, it is obvious that both pilots and potential pilots take the strength of the hiring market into strong account when deciding whether to invest in training, but the actual supply of new commercial pilots is affected only several years later when the hiring market may be entirely different. By the time the first hiring boom reached its peak in 2000, hiring had been increasing very steadily for six years. Accordingly, the number of CPLs issued had increased since 1997, and there was a rather steady supply of new pilots that prevented the boom from ever becoming a severe shortage. Even if 9/11 and the dot com implosion never happened, I suspect that flight training could've easily kept up with airline growth and retirements. There is a lot of flight training infrastructure in this country that can be utilized when times are good and people choose to invest in flight training (incidentally, the lack of such infrastructure is why the pilot shortage is very real in overseas emerging markets). I seriously doubt that any extended period of growth and retirements will translate into a severe, prolonged pilot shortage.

By the time the first hiring boom reached its peak in 2000, hiring had been increasing very steadily for six years. Accordingly, the number of CPLs issued had increased since 1997, and there was a rather steady supply of new pilots that prevented the boom from ever becoming a severe shortage. Even if 9/11 and the dot com implosion never happened, I suspect that flight training could've easily kept up with airline growth and retirements. There is a lot of flight training infrastructure in this country that can be utilized when times are good and people choose to invest in flight training (incidentally, the lack of such infrastructure is why the pilot shortage is very real in overseas emerging markets). I seriously doubt that any extended period of growth and retirements will translate into a severe, prolonged pilot shortage.The boom of 2007 was different. Although airline hiring had increased between 2002 and 2006, it was not the sort of steady growth across all sectors that characterized 1994-2000, and it was a period of instability for the airlines. The woes of the legacies and the plights of their pilots - contracts gutted and pensions terminated in bankruptcy - were very much in the news. These are not the conditions that inspire people to sign up for flight training. Accordingly, CPL issuances reached their post-9/11 nadir in 2006 and posted only a modest gain in 2007. When the regional airlines suddenly had to hire 6800 pilots in 2007 - double that of 2006 and 235% more than Air, Inc had predicted at the beginning of the year - several years of depressed training translated into a dearth of qualified pilots. Hiring minimums plummeted, and those airlines with the highest attrition (i.e., most pilot-unfriendly management) were forced to hire pilots with the minimum legal qualifications - and they still couldn't find enough pilots. If this hiring environment had continued - if high oil prices and the economy hadn't killed of the demand for pilots - it is likely that CPL issuances would've continued the upswing seen in 2007-2008 and eventually satisfied the industry's demand for pilots. In the meantime, though, the shortage would've posed a distinct challenge for the airline industry and a distinct opportunity for pilots.

So what does the future hold? I think 2009 is going to be a very rough year for airline pilots. Although oil prices have fallen significantly, it's anybody's guess as to when and where the economy will bottom out and begin its recovery. All the airlines are forecasting significantly decreased revenue for next year; many forecasts have revenue falling more than in 1987, 1991, or 2001-2002. Accordingly, the airlines have made significant capacity cuts with more probably on the way. To the airlines' advantage, the credit crunch should ensure there are no upstarts to play spoiler by increasing overall capacity like in 2001-2006, but this also means there will likely be no hiring at low cost carriers to absorb the legacies' furloughees. Many regional airlines, too, are facing contraction as their major airline partners try to reduce their exposure to 30-50 seat RJs. Meanwhile, the change to the retirement age means retirements will be significantly below normal until 2012. My guess is that overall hiring for 2009 will be significantly lower than 2002, with a depressed job market for several years after that.

Eventually, though, the shortage at the regionals we saw in 2007 will return, and it will be worse next time. Although CPL issuances will continue to rise for another one or two years, after that you'll see a sharp drop like that in 2003. I think the training slump will be much lower than it was in 2003-2006. Back then, there were still jobs available at the regionals even if the majors were still in turmoil; this time there will be few airline jobs of any description for several years straight. The cost of flight training has increased significantly in the last few years. It will also be harder to secure loans for flight training as long as the credit crunch endures. During the next few years, there will be a lot of people stuck flight instructing, flying freight, etc, but this surplus will only obscure the fact that there are fewer and fewer new pilots being trained.

When the economy begins its recovery and the airlines start adding capacity back into their systems - several years from now, I'm guessing - they will initially have no problem finding qualified candidates for their openings. The majors, of course, will hire from the huge cadre of regional airline captains chomping at the bit to move up to the next level, and the regionals will be able to draw from the pool of flight instructors and freight dogs that formed during the years without airline hiring. If the hiring ramped up slowly and steadily, I would expect the training of new pilots to increase enough by the time this pool is depleted that the boom would never become a shortage. There is a complicating factor, though: the first wave of airline pilots to hit age 65 will retire in 2012 and double or even triple the annual number of retirements. If this happens concurrently with an industry growth period, attrition at the regionals will skyrocket and quickly deplete the pool of experienced pilots. I think you'll see a very similar shortage to 2007, but without several years of preceding hiring activity like 2004-2006 to stimulate new training. You'll see a return of 250 hour commercial pilots to the right seat of airliners (or even less qualified, if the ATA gets it's way on Multi-Pilot License). You'll also see a return of signing bonuses for experienced pilots. This situation will persist for several years until the people it lures into aviation complete their training. It will be a unique opportunity for regional pilots to get better contracts without fear that their flying will be replaced by a lower-cost regional.

In the meantime, those of us at the regionals aren't going anywhere - if we're lucky. I personally don't have a great deal of faith that I'll be employed at NewCo this time next year, in the left seat anyways. If that happens, there's a good chance I'll be heading overseas - where the pilot shortage is very real indeed and still ongoing, and a pilots' services are therefore valued more highly than in the erstwhile "land of opportunity".

Monday, December 08, 2008

Earning My Keep

On Friday I was in San Antonio on a long layover; we had a van time of 4:45pm for a 5:51pm departure to Minneapolis. I slept in that morning and woke too late to do anything interesting like go to the Alamo or Riverwalk. Around noon I met Brent, my FO, in the lobby, and we walked over to Bill Miller's BBQ for their wonderful chopped pork sandwich platter. Over lunch, we had a conversation wherein Brent said something interesting that sparked an idea for a blog post. As soon as I got back to the hotel room I pulled out my notebook and began writing.

I should have given the idea more time to percolate before I started. I wrote several pages of disjointed paragraphs full of half-baked ideas and contradictory proclamations, despaired on my first reading, threw the pages away, and started over with a new preliminary outline. The post I sketched out didn't seem much better than the one in the trash can. I wanted to write a thoughtful essay about the thorny subject of pilot pay. I wanted to move beyond the usual arguments about being overpaid or underpaid and explore the question of what exactly pilot pay is really based on. Is it knowledge? Experience? Certificates? Responsibility for lives and property? Ability of the aircraft to generate revenue? Difficulty of the job? A life spent on the road? Negotiating leverage? Free market value? I doubted whether there's really any subjective answer; you'd certainly get differing opinions from pilots, management, unions, and the traveling public. The framework for an interesting essay was there but I was getting nowhere in fleshing it out. I realized that I've written enough on the subject over the years that I should only return to it if I have something to add. Also, most of my readers are a whole lot less interested in the question of whether I'm paid enough than I am, so any further exposition on the subject ought to at least reward the reader with decent writing. This clearly was not it. Frustrated, I set the notebook aside and did a crossword puzzle instead.

At 4:20 I repacked and changed into my uniform and then met my crew in the lobby; we departed for the airport on time and arrived at the gate just as the inbound crew disembarked. They reported that the ship was "clean" and the ride was good. I checked the radar online; an icy blue smear nearing Minneapolis provided the first clue of things to come. Sure enough, the TAF called for snow to begin falling before our arrival, although visibility and ceiling were respectively forecast to stay above one and a half mile and 1500 feet. Our alternate was LaCrosse, Wisconsin, a small airport about 100 miles southeast of Minneapolis with a similar forecast. Our dispatcher thoughtfully provided us with 800 pounds of holding fuel along with 1500 pounds of contingency fuel. The difference between the two is a fine but important distinction. Holding fuel is considered part of the "minimum fuel load" listed on the release, while contingency fuel provides an additional buffer above the legal minimum.

The departure from San Antonio was uneventful; Brent was flying the leg. This was day three of a four day trip, Brent had several hundred hours in the airplane, and I was comfortable with him landing on a snow-covered runway in Minneapolis. On a leg like this, where there are clues that some Captainly wiliness might be required, I'd just as soon be non-flying pilot anyways. As the western sky grew dim, I set the ACARS up to automatically retrieve the Minneapolis ATIS every time it was updated.

The first two hours of the flight were quiet except for the frequent annunciation of a new ATIS. The snowfall dropped the visibility to three quarters of a mile at first but then it rose and held steady at around one and a half miles; the ceiling stayed pretty high. We could clearly get in but my Captain's antennae were still beginning to twitch. For starters, nearly every ATIS update - specials were coming out every 20 minutes - showed runways 12R and 12L being alternately closed for snow removal. Minneapolis cannot function on one arrival runway without significant delays, as the construction on 30L/12R so convincingly proved in 2006. I decided to climb and slow down a bit to save fuel. We checked on with Minneapolis Center with nary a word of delays. By the time we turned over Fort Dodge IA onto the TWOLF One arrival, I thought that perhaps we'd dodge the bullet yet.

"Newco 1917, got a new route for delays into Minneapolis, advise ready to copy." I groaned and grabbed the clearance printout and a pen. "Newco 1917, cleared to Minneapolis via Sioux Falls, Redwood Falls, SKETR Three arrival." Whoa. I knew Sioux Falls was quite a ways northwest of our position. I pecked "FSD" into the FMS and requested a direct track; sure enough, it appeared on the moving map nearly 90 degrees to our left and over 100 miles away. As soon as I inputted the rest of the arrival, I started crunching the fuel numbers. They weren't pretty; the reroute had decimated our contingency fuel and added nearly 30 minutes to our flight. I texted the new routing and landing fuel to our dispatcher via ACARS.

The flight plan attached to our release normally tells us minimum fuel for each waypoint, but we were no longer on our planned route so I had to work up new numbers. I started with my personal fuel minimum for arrival at MSP. In this case it happened to coincide with the dispatcher-calculated minimum of 5400 lbs, only because of the 800 lbs of holding fuel. If we ended up holding, the dispatcher might amend the release to turn the holding fuel into contingency fuel, reducing our minimum fuel at MSP to 4600 lbs (2400 lbs fuel burn to our alternate plus 2200 lbs reserve). If that happened, however, my personal minimum at MSP would remain 5400 lbs because there's no way I'm going to be shooting an approach in crummy weather at the alternate with less than 3000 lbs in my tanks. After all, the company defines 3000 lbs as a "minimum fuel state" and 2000 lbs as an "emergency fuel state." Working backwards from MSP, I calculated the minimum fuel number for several waypoints on the arrival. Crossing Sioux Falls, we were only 400 lbs above the minimum. As we turned eastbound again, I told Brent to slow down more to take advantage of the strong tailwind and save fuel.

"Newco 1917, holding instructions for delays into Minneapolis...hold southwest of SHONN as published at flight level 350, leg lengths your discretion, expect further clearance 0253 zulu, time now 0205 zulu." I read back the clearance but added "We'll have to run the numbers and get back to you on our fuel state." We were going to arrive at SHONN nearly 30 minutes before our EFC time, with only 500 lbs over the minimum fuel at SHONN. I told ATC we had enough fuel for perhaps 10 minutes of holding before diverting and asked if Minneapolis Approach might take that into consideration. The controller sounded doubtful but said he'd check.

I texted the news to our dispatcher along with a request for updated weather at KLSE as well as KRST. My thinking was that if the weather was good enough at Rochester, we could make it our new alternate; since it's closer to MSP, the decreased fuel burn to the alternate would free up some fuel for holding. Our dispatcher responded with weather for Rochester and Brainerd, about 100 miles northwest of MSP, but not LaCrosse, and asked me to pick KRST or KBRD as my new alternate. Rochester had 3/4 mile visibility, actually below alternate minimums. Brainerd was better but almost as far away as LaCrosse. I texted that I'd just keep KLSE, and the dispatcher responded by informing me that LaCrosse was down so he was changing my alternate to KBRD. Ah...okay then. It didn't save me any fuel but at least the weather was nice there!

We were rapidly approaching SHONN so it was time to tell the passengers something. I wasn't going to mention the possibility of diverting just yet, but they had to be wondering why we weren't on the ground yet. "Folks, from the flight deck...that forecast snow in Minneapolis showed up a few hours ago and is making a pretty good mess of things, with lots of delays going into MSP. We were given a reroute over Sioux Falls which helped, but air traffic control still needs us to hold over a point about 50 miles southwest of MSP for up to a half hour...." I glanced at Brent who was gesturing wildly to me and released the PA button in time to hear ATC cancel our hold. "...Uh, nevermind folks, they just cleared us to come on in, hopefully without much further delay. Flight attendants please prepare for arrival."

We made up some more fuel between SHONN and the airport thanks to our slowed speed, the tailwind, a delayed descent, and an early vector to the downwind. ATC put us on a nearly 30 mile final for runway 12L; 12R was closed for snow removal. We were another 15 miles along when ATC broke us and a preceding NewCo flight off the approach because another aircraft reported nil braking, closing the runway until the snowplows could clear it. The other NewCo flight diverted to their alternate immediately. I told approach we had a little fuel to work with so long as there wasn't much delay in opening 12R. They assured us it'd be open soon and resequenced us onto a 20 mile final.

This time we got almost to the FAF before approach control again broke us off the approach; the snowplows weren't going to have quite enough time to get off the runway. I reconsidered our fuel status. The fuel burn to Brainerd was 2200 lbs, so I wanted at least 5200 lbs on landing. We had a few hundred more than that, enough for six minutes or so. "We can take another go if it's a short final, otherwise we need to go to Brainerd." ATC assured us they'd keep us close in and they lived up to their word. We got the runway in sight a few miles out, and Brent made a nicely firm landing. Despite the heavy use of thrust reversers, the ship was rather slow to decelerate; as soon as I took the controls, I could see why. The runway was quite slick though it had just been plowed. The anti-skid surged in and out rapidly as I mashed down hard on the brake pedals, a rather unnatural act of faith. I slowed to a nearly complete stop before even beginning the turn off the runway, and just as well, for the taxiways hadn't been cleared recently. The centerlines were buried so I stayed in other planes' tracks on the way to the gate. The airport was eerily calm, and I thought that it looked like a ghost town with a two inch layer of chalky dust covering the abandoned wagons and buggies.

No time for such fantasies; we were pretty late getting in, and due out to Missoula in less than a half hour. Almost as soon as our passengers were deplaned, new ones trudged wearily onboard. Brent and I went through our familiar preflight dance efficiently, with the addition of a radio call to the Iceman. Paperwork complete and handed out with a wave to the harried gate agent; door slams shut, made up some time on the turn. We taxied out, got deiced, and took off into a post-apocalyptic orange-hued overcast with snowflake constellations warping past in the momentary glare of our landing lights.

Not until we settled into the reverie of a darkened cockpit in cruise did my thoughts wander back to the previous flight. Pretty uneventful, really - got delayed a bit, decided we had enough fuel, landed. Lots of other planes out doing the same thing, and lots of other snowy nights left in this Minnesota winter. To be sure, the events of the flight drew upon my knowledge, experience, and judgment much more than your average sunny-day flight. Truth is, if every day was sunny and trouble-free, a monkey could do my job. But they are not, so he cannot. It takes an army of well-trained, experienced pilots to keep the fleet flying safety and efficiently in all sorts of conditions. The fact that flying is so routine, so safe - the fact that flights like the last one barely merit mention - is perversely held up as proof that a pilot's job is easy and pilots are overpaid!

So are pilots today underpaid? I think so, but plenty of others disagree. I can tell you this: the current level of pilot compensation is not attracting many new people into the industry. We saw a glimpse of the consequences as recently as this summer, when regional airlines were so short on qualified applicants that they were hiring 250 hour freshly minted commercial pilots into the right seats of RJs captained by 2000 hour freshly minted ATPs. The pendulum has since swung the other way, and there are thousands of qualified pilots on the streets looking for nonexistant jobs this holiday season. There are not, however, that many people taking out $60,000 loans to learn to fly these days, so the pilot shortage will return with a vengeance when the current economic distress subsides. When that happens, I would think twice about putting oneself or one's family on a regional jet on any dark and snowy winter night.

I should have given the idea more time to percolate before I started. I wrote several pages of disjointed paragraphs full of half-baked ideas and contradictory proclamations, despaired on my first reading, threw the pages away, and started over with a new preliminary outline. The post I sketched out didn't seem much better than the one in the trash can. I wanted to write a thoughtful essay about the thorny subject of pilot pay. I wanted to move beyond the usual arguments about being overpaid or underpaid and explore the question of what exactly pilot pay is really based on. Is it knowledge? Experience? Certificates? Responsibility for lives and property? Ability of the aircraft to generate revenue? Difficulty of the job? A life spent on the road? Negotiating leverage? Free market value? I doubted whether there's really any subjective answer; you'd certainly get differing opinions from pilots, management, unions, and the traveling public. The framework for an interesting essay was there but I was getting nowhere in fleshing it out. I realized that I've written enough on the subject over the years that I should only return to it if I have something to add. Also, most of my readers are a whole lot less interested in the question of whether I'm paid enough than I am, so any further exposition on the subject ought to at least reward the reader with decent writing. This clearly was not it. Frustrated, I set the notebook aside and did a crossword puzzle instead.

At 4:20 I repacked and changed into my uniform and then met my crew in the lobby; we departed for the airport on time and arrived at the gate just as the inbound crew disembarked. They reported that the ship was "clean" and the ride was good. I checked the radar online; an icy blue smear nearing Minneapolis provided the first clue of things to come. Sure enough, the TAF called for snow to begin falling before our arrival, although visibility and ceiling were respectively forecast to stay above one and a half mile and 1500 feet. Our alternate was LaCrosse, Wisconsin, a small airport about 100 miles southeast of Minneapolis with a similar forecast. Our dispatcher thoughtfully provided us with 800 pounds of holding fuel along with 1500 pounds of contingency fuel. The difference between the two is a fine but important distinction. Holding fuel is considered part of the "minimum fuel load" listed on the release, while contingency fuel provides an additional buffer above the legal minimum.

The departure from San Antonio was uneventful; Brent was flying the leg. This was day three of a four day trip, Brent had several hundred hours in the airplane, and I was comfortable with him landing on a snow-covered runway in Minneapolis. On a leg like this, where there are clues that some Captainly wiliness might be required, I'd just as soon be non-flying pilot anyways. As the western sky grew dim, I set the ACARS up to automatically retrieve the Minneapolis ATIS every time it was updated.

The first two hours of the flight were quiet except for the frequent annunciation of a new ATIS. The snowfall dropped the visibility to three quarters of a mile at first but then it rose and held steady at around one and a half miles; the ceiling stayed pretty high. We could clearly get in but my Captain's antennae were still beginning to twitch. For starters, nearly every ATIS update - specials were coming out every 20 minutes - showed runways 12R and 12L being alternately closed for snow removal. Minneapolis cannot function on one arrival runway without significant delays, as the construction on 30L/12R so convincingly proved in 2006. I decided to climb and slow down a bit to save fuel. We checked on with Minneapolis Center with nary a word of delays. By the time we turned over Fort Dodge IA onto the TWOLF One arrival, I thought that perhaps we'd dodge the bullet yet.

"Newco 1917, got a new route for delays into Minneapolis, advise ready to copy." I groaned and grabbed the clearance printout and a pen. "Newco 1917, cleared to Minneapolis via Sioux Falls, Redwood Falls, SKETR Three arrival." Whoa. I knew Sioux Falls was quite a ways northwest of our position. I pecked "FSD" into the FMS and requested a direct track; sure enough, it appeared on the moving map nearly 90 degrees to our left and over 100 miles away. As soon as I inputted the rest of the arrival, I started crunching the fuel numbers. They weren't pretty; the reroute had decimated our contingency fuel and added nearly 30 minutes to our flight. I texted the new routing and landing fuel to our dispatcher via ACARS.

The flight plan attached to our release normally tells us minimum fuel for each waypoint, but we were no longer on our planned route so I had to work up new numbers. I started with my personal fuel minimum for arrival at MSP. In this case it happened to coincide with the dispatcher-calculated minimum of 5400 lbs, only because of the 800 lbs of holding fuel. If we ended up holding, the dispatcher might amend the release to turn the holding fuel into contingency fuel, reducing our minimum fuel at MSP to 4600 lbs (2400 lbs fuel burn to our alternate plus 2200 lbs reserve). If that happened, however, my personal minimum at MSP would remain 5400 lbs because there's no way I'm going to be shooting an approach in crummy weather at the alternate with less than 3000 lbs in my tanks. After all, the company defines 3000 lbs as a "minimum fuel state" and 2000 lbs as an "emergency fuel state." Working backwards from MSP, I calculated the minimum fuel number for several waypoints on the arrival. Crossing Sioux Falls, we were only 400 lbs above the minimum. As we turned eastbound again, I told Brent to slow down more to take advantage of the strong tailwind and save fuel.

"Newco 1917, holding instructions for delays into Minneapolis...hold southwest of SHONN as published at flight level 350, leg lengths your discretion, expect further clearance 0253 zulu, time now 0205 zulu." I read back the clearance but added "We'll have to run the numbers and get back to you on our fuel state." We were going to arrive at SHONN nearly 30 minutes before our EFC time, with only 500 lbs over the minimum fuel at SHONN. I told ATC we had enough fuel for perhaps 10 minutes of holding before diverting and asked if Minneapolis Approach might take that into consideration. The controller sounded doubtful but said he'd check.

I texted the news to our dispatcher along with a request for updated weather at KLSE as well as KRST. My thinking was that if the weather was good enough at Rochester, we could make it our new alternate; since it's closer to MSP, the decreased fuel burn to the alternate would free up some fuel for holding. Our dispatcher responded with weather for Rochester and Brainerd, about 100 miles northwest of MSP, but not LaCrosse, and asked me to pick KRST or KBRD as my new alternate. Rochester had 3/4 mile visibility, actually below alternate minimums. Brainerd was better but almost as far away as LaCrosse. I texted that I'd just keep KLSE, and the dispatcher responded by informing me that LaCrosse was down so he was changing my alternate to KBRD. Ah...okay then. It didn't save me any fuel but at least the weather was nice there!

We were rapidly approaching SHONN so it was time to tell the passengers something. I wasn't going to mention the possibility of diverting just yet, but they had to be wondering why we weren't on the ground yet. "Folks, from the flight deck...that forecast snow in Minneapolis showed up a few hours ago and is making a pretty good mess of things, with lots of delays going into MSP. We were given a reroute over Sioux Falls which helped, but air traffic control still needs us to hold over a point about 50 miles southwest of MSP for up to a half hour...." I glanced at Brent who was gesturing wildly to me and released the PA button in time to hear ATC cancel our hold. "...Uh, nevermind folks, they just cleared us to come on in, hopefully without much further delay. Flight attendants please prepare for arrival."

We made up some more fuel between SHONN and the airport thanks to our slowed speed, the tailwind, a delayed descent, and an early vector to the downwind. ATC put us on a nearly 30 mile final for runway 12L; 12R was closed for snow removal. We were another 15 miles along when ATC broke us and a preceding NewCo flight off the approach because another aircraft reported nil braking, closing the runway until the snowplows could clear it. The other NewCo flight diverted to their alternate immediately. I told approach we had a little fuel to work with so long as there wasn't much delay in opening 12R. They assured us it'd be open soon and resequenced us onto a 20 mile final.

This time we got almost to the FAF before approach control again broke us off the approach; the snowplows weren't going to have quite enough time to get off the runway. I reconsidered our fuel status. The fuel burn to Brainerd was 2200 lbs, so I wanted at least 5200 lbs on landing. We had a few hundred more than that, enough for six minutes or so. "We can take another go if it's a short final, otherwise we need to go to Brainerd." ATC assured us they'd keep us close in and they lived up to their word. We got the runway in sight a few miles out, and Brent made a nicely firm landing. Despite the heavy use of thrust reversers, the ship was rather slow to decelerate; as soon as I took the controls, I could see why. The runway was quite slick though it had just been plowed. The anti-skid surged in and out rapidly as I mashed down hard on the brake pedals, a rather unnatural act of faith. I slowed to a nearly complete stop before even beginning the turn off the runway, and just as well, for the taxiways hadn't been cleared recently. The centerlines were buried so I stayed in other planes' tracks on the way to the gate. The airport was eerily calm, and I thought that it looked like a ghost town with a two inch layer of chalky dust covering the abandoned wagons and buggies.

No time for such fantasies; we were pretty late getting in, and due out to Missoula in less than a half hour. Almost as soon as our passengers were deplaned, new ones trudged wearily onboard. Brent and I went through our familiar preflight dance efficiently, with the addition of a radio call to the Iceman. Paperwork complete and handed out with a wave to the harried gate agent; door slams shut, made up some time on the turn. We taxied out, got deiced, and took off into a post-apocalyptic orange-hued overcast with snowflake constellations warping past in the momentary glare of our landing lights.

Not until we settled into the reverie of a darkened cockpit in cruise did my thoughts wander back to the previous flight. Pretty uneventful, really - got delayed a bit, decided we had enough fuel, landed. Lots of other planes out doing the same thing, and lots of other snowy nights left in this Minnesota winter. To be sure, the events of the flight drew upon my knowledge, experience, and judgment much more than your average sunny-day flight. Truth is, if every day was sunny and trouble-free, a monkey could do my job. But they are not, so he cannot. It takes an army of well-trained, experienced pilots to keep the fleet flying safety and efficiently in all sorts of conditions. The fact that flying is so routine, so safe - the fact that flights like the last one barely merit mention - is perversely held up as proof that a pilot's job is easy and pilots are overpaid!

So are pilots today underpaid? I think so, but plenty of others disagree. I can tell you this: the current level of pilot compensation is not attracting many new people into the industry. We saw a glimpse of the consequences as recently as this summer, when regional airlines were so short on qualified applicants that they were hiring 250 hour freshly minted commercial pilots into the right seats of RJs captained by 2000 hour freshly minted ATPs. The pendulum has since swung the other way, and there are thousands of qualified pilots on the streets looking for nonexistant jobs this holiday season. There are not, however, that many people taking out $60,000 loans to learn to fly these days, so the pilot shortage will return with a vengeance when the current economic distress subsides. When that happens, I would think twice about putting oneself or one's family on a regional jet on any dark and snowy winter night.

Sunday, November 30, 2008

Out East

Almost as soon as we were through 10,000 feet, I had my atlas out. It was completely clear along our route - a rarity in November - and on the dark, moonless night, every light for hundreds of miles was visible. Every town and road printed on the map was duplicated in orange and white pixels below. From Memphis we headed northeastwards on J42, toward Nashville. It grew steadily brighter until we passed overhead; then the glow of suburbia quickly gave way to the isolated pinpricks of eastern Kentucky's rural hill country. Louisville floated by to our left; to our right, Knoxville illuminated the spine of the Great Smokey Mountains. My First Officer broke the silence to point out his hometown where Tennessee, Kentucky, and Virginia all come together. At Beckley, WV, we made a slight right to cross the Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians just north of I-64. A thin band of light stretching as far as the eye could see marked the Great Valley; the dark band after that, the Blue Ridge. We reentered "civilization" over Charlottesville, VA, the pixels becoming ever thicker and brighter as we approached Washington DC. From 35,000 feet, we could clearly make out the dark National Mall and the floodlit Capitol Building. As we passed over Chesapeake Bay into Delaware, I noted how Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia, Newark, and New York essentially form one contiguous, enormous metropolis. The Jersey shore, to our right, was much darker but the casinos of Atlantic City shone brightly, prompting my FO to reminisce about his freight dog days flying into ACY. Now New York's glow, visible 200 miles prior, hardened and formed into city and water, then the individual boroughs, and then mile after mile of individual streets and buildings. I picked out the Empire State and Chrysler Buildings as we overflew JFK and LGA. At the Connecticut coast we turned right; the moonless night and dark waters of Long Island Sound made me think of JFK, Jr. By now we were on our descent; the arrival took us over Providence, RI, which until then had always been a fuzzy spot in my geographical knowledge. We went "feet wet" above the spot that the Pilgrims went "feet dry." The vectors to final took us far out over the Atlantic, almost to the tip of Cape Cod. Our 150 minute night tour of the east coast concluded with a nice view of the Boston skyline from the final approach to runway 27.

Prior to flying for NewCo, I had spent very little time "out east." In fact, the furthest east I'd flown was Grand Rapids, MI, and that was on a cross-country flight I did in college! My subsequent flight instructing, freight dogging, and airline flying was all on the west coast. At Horizon, the easternmost destination for the Q400 was Billings, MT. At NewCo, the majority of our destinations are east of the Mississippi. On the east coast proper, we fly to MHT, BOS, JFK, LGA, EWR, PHL, BWI, IAD, RIC, ORF, CLT, JAX, and MCO. When I began flying to these places, my geographic knowledge was sorely lacking. Now all the pieces are starting to fit together.

When I was flying out west, I had no idea just how good I had it. Flying on the east coast in a royal pain. Out west, it's Direct-To everywhere and talk to ATC once every 20 minutes to change frequencies. Out east, it's nonstop convoluted reroutes, last-minute crossing altitude restrictions, and an endless litany of frequency changes. You eventually give up even trying to check in with certain sectors after having your check in stepped on half a dozen times. Airports like PHL, EWR, LGA, and JFK are delay-prone on good days; throw in some bad weather and you're going nowhere quick. Those airports make me thankful that our turd of a contract at least has "Block or Better" pay.* Our hotels at eastern layovers tend to be in decrepit industrial areas near the airport, and the shuttle van drivers are often surly and hurried.

Despite all that, I still enjoy going east. I guess the novelty just hasn't worn off yet. I enjoy the aerial sightseeing when the weather cooperates. The Appalachians, Catskills, and Adirondacks, while less starkly grand than the Rockies, Sierras, and Cascades, have great natural beauty of their own. The human geography, too, is interesting to me: the patchwork quilt-like farmsteads of rural areas, the little towns secluded in dead-end valleys miles from anywhere, the seemingly endless cities of the BosWash corridor. There's a lot of history out east; I enjoy having a birds-eye view of the landscape that famous battles and campaigns were waged across.

On the ground, there's a lot to do if you make the effort. I haven't spent much time in most of the cities we go to, so they invite exploration. The morning after my sightseeing flight up the eastern seaboard, I woke up early and hopped on the subway to downtown Boston. I reemerged at Boston Common, America's oldest park, and started following the red brick path of the Freedom Trail. It was fascinating to see so many important historical sites in the course of a fairly short stroll. The South Meeting House, the Old State House, Old North Church, and Bunker Hill are all legendary places I've heard about since grade school but have never seen for myself. Walking in and around them made the history seem more real, more palpable; I felt new appreciation for the vision and courage of men like Joseph Warren, Samuel Adams, and Paul Revere.

I have a long Philadelphia layover coming up soon. I hope to make it to the Revolution-era sights there. If they're anywhere nearly as interesting as the Freedom Trail in Boston, it should take some of the sting out of having to operate out of PHL.

*"Block or Better" means that we are paid the greater of scheduled or actual block time. Therefore, when we're delayed we get paid extra, but we don't get shorted for being early. Although Horizon has a much better contract than NewCo, they did not have Block or Better; I got paid based only on the historical block time for the leg (usually less than scheduled block), with no additional compensation for overblocking. If Horizon flew into JFK, LGA, or PHL, that'd be a very bad thing to have in the contract.

Prior to flying for NewCo, I had spent very little time "out east." In fact, the furthest east I'd flown was Grand Rapids, MI, and that was on a cross-country flight I did in college! My subsequent flight instructing, freight dogging, and airline flying was all on the west coast. At Horizon, the easternmost destination for the Q400 was Billings, MT. At NewCo, the majority of our destinations are east of the Mississippi. On the east coast proper, we fly to MHT, BOS, JFK, LGA, EWR, PHL, BWI, IAD, RIC, ORF, CLT, JAX, and MCO. When I began flying to these places, my geographic knowledge was sorely lacking. Now all the pieces are starting to fit together.

When I was flying out west, I had no idea just how good I had it. Flying on the east coast in a royal pain. Out west, it's Direct-To everywhere and talk to ATC once every 20 minutes to change frequencies. Out east, it's nonstop convoluted reroutes, last-minute crossing altitude restrictions, and an endless litany of frequency changes. You eventually give up even trying to check in with certain sectors after having your check in stepped on half a dozen times. Airports like PHL, EWR, LGA, and JFK are delay-prone on good days; throw in some bad weather and you're going nowhere quick. Those airports make me thankful that our turd of a contract at least has "Block or Better" pay.* Our hotels at eastern layovers tend to be in decrepit industrial areas near the airport, and the shuttle van drivers are often surly and hurried.

Despite all that, I still enjoy going east. I guess the novelty just hasn't worn off yet. I enjoy the aerial sightseeing when the weather cooperates. The Appalachians, Catskills, and Adirondacks, while less starkly grand than the Rockies, Sierras, and Cascades, have great natural beauty of their own. The human geography, too, is interesting to me: the patchwork quilt-like farmsteads of rural areas, the little towns secluded in dead-end valleys miles from anywhere, the seemingly endless cities of the BosWash corridor. There's a lot of history out east; I enjoy having a birds-eye view of the landscape that famous battles and campaigns were waged across.

On the ground, there's a lot to do if you make the effort. I haven't spent much time in most of the cities we go to, so they invite exploration. The morning after my sightseeing flight up the eastern seaboard, I woke up early and hopped on the subway to downtown Boston. I reemerged at Boston Common, America's oldest park, and started following the red brick path of the Freedom Trail. It was fascinating to see so many important historical sites in the course of a fairly short stroll. The South Meeting House, the Old State House, Old North Church, and Bunker Hill are all legendary places I've heard about since grade school but have never seen for myself. Walking in and around them made the history seem more real, more palpable; I felt new appreciation for the vision and courage of men like Joseph Warren, Samuel Adams, and Paul Revere.

I have a long Philadelphia layover coming up soon. I hope to make it to the Revolution-era sights there. If they're anywhere nearly as interesting as the Freedom Trail in Boston, it should take some of the sting out of having to operate out of PHL.

*"Block or Better" means that we are paid the greater of scheduled or actual block time. Therefore, when we're delayed we get paid extra, but we don't get shorted for being early. Although Horizon has a much better contract than NewCo, they did not have Block or Better; I got paid based only on the historical block time for the leg (usually less than scheduled block), with no additional compensation for overblocking. If Horizon flew into JFK, LGA, or PHL, that'd be a very bad thing to have in the contract.

Friday, November 21, 2008

The Iceman Cometh

Well, there's no escaping it now. Minnesota has had several days of snow, although none of it lasted more than a few hours; it's currently 12 degrees in Minneapolis. When I got done with a trip yesterday morning, my short walk from the bus stop to our apartment froze my fingers and ears so thoroughly that I didn't venture outside again all day. My six month hibernation begins now.

If I could spend the entire winter curled up inside with a warm blanket and hot chocolate I very possibly would, but alas, the need to earn a living saves me from being a total recluse during winter. Being a pilot is a good job for someone who hates long cold winters but lives in Minnesota, as it gets me above the clouds into sunshine rather frequently and also involves the occasional layover in Phoenix or San Antonio. Unfortunately two of RedCo's three hubs are in northern states, so I do spend a lot of time operating in wintry conditions. This rather frequently involves deicing. I deiced for the first time of the season about a month ago. Given that I hadn't done it since last winter, I took that as my cue to open our Deicing/Anti-icing manual and study up.

As I mentioned in my last post, anti-icing systems on jets are beautifully effective in flight but provide no protection on the ground. For that, we use propylene glycol-based deicing fluids somewhat similar to the antifreeze fluid used in your car. Similar fluids have been used in aviation for quite a while, but for a long time they were poorly understood and their use was nonstandard throughout the industry. After some notable accidents involving airliners attempting takeoff with iced-up wings, the FAA got serious about ground deicing. Now every Part 121 carrier is required to maintain and distribute an FAA-approved Ground Deicing/Anti-icing Manual. It spells out in great detail the various ground and flight crew roles and responsibilities, what parts of the aircraft must be "clean" for takeoff, approved methods of removing contamination, the limitations of various anti-ice fluids, and the checks that must be accomplished before an airplane may take off.

As the name of the manual suggests, there are two stages to ground deicing/anti-icing. Deicing is intended to remove any previously accumulated contaminants that are adhering to the airframe. This may include frost, freezing rain, snow, or airframe ice from the last flight. Anti-icing prevents further accumulation of freezing precipitation between deicing and takeoff. In very mild conditions, both of these steps may be accomplished in a single application of deicing fluid, but more often the steps are accomplished with separate coats of different fluids.

The deice fluid used to remove previous contaminants is called Type I fluid. It is fairly thin, slippery, and is dyed red to help deicing personnel see which parts of the aircraft have already been sprayed. Type I fluid is normally heated between 130 and 180 degrees F, and is sprayed out at considerable pressure to aid in knocking contaminants off the airframe. As Type I fluid isn't very viscous, it doesn't adhere to the airframe well. It also has a somewhat limited ability to absorb moisture. For both of these reasons, Type I fluid is used for anti-icing purposes only for short periods or in very light ground icing conditions.

The more commonly used anti-ice fluid is called Type IV. It has thickening agents added and is dyed green. Type IV is always applied cold after a previous application of Type I fluid. It is sometimes diluted with water, not only to save costs but also to (rather counter-intuitively) lower its freezing point. A solution of 75% fluid and 25% water has a freezing point of around -55C; undiluted fluid has around the same -30C freezing point as a 50-50 mix. Type IV fluid's greater viscosity helps it to better adhere to the airframe. It is designed to shear off at around 100 knots airspeed on the takeoff roll, leaving a clean wing. It also has greater moisture absorption capabilities than Type I fluid. All this means that it protects the airframe against contamination for much longer periods than Type I fluid.

The most common apparatus used to spray deicing fluid is a boom truck. The truck drives around the aircraft while the deicer sprays the fluid from a basket on top of the boom. Both Type I and Type IV fluid can be and often are sprayed from the same truck in subsequent applications. A fairly recent development is infrared deicing. Infrared deicers melt existing snow and ice off the airframe as the plane taxies through a hangar-like structure. This arrangement still requires a truck to spray Type IV fluid for anti-ice protection. There are only a few infrared deice installations in the US.

Occasionally ground crews will deice aircraft before the flight crew arrives in the morning if there was frost or snow accumulation overnight but ground icing no longer exists. Usually, though, crews must request deicing. At small stations, the ground crew needs advance warning to make sure the truck has enough fluid and to heat it up. If there are any contaminants adhering to the airframe, or if there's steady snowfall, the decision to deice is an easy one. It's less clear when the temperatures are just warm enough that the snow is melting on contact, or if flurries aren't quite sticking to the airframe. You don't want to deice unnecessarily due to the time and cost involved, but you also don't want changing conditions to make you come back for deicing at the last minute either.

At outstations, I'll inform operations or a member of the ground crew that we need to deice at least 30 minutes before departure. At most of these airports, we get deiced right after pushback from our gate, before we've started our engines. At the smallest stations, the same rampers that just loaded the bags and pushed us back will then hop in the deice truck. At large northern outstations and hub airports, there are dedicated deice pads located near the end of the runways and manned by a virtual army of trucks and staff during winter weather. At Minneapolis, there are four deice pads that can each handle half a dozen aircraft simultaneously! The usual drill is to call "The Iceman," or central coordinator, as soon as you know you'll need deicing. They'll either assign you a pad or dispatch a truck to deice you near the gate when you push back. If assigned a pad, you confirm it with the Iceman when you begin taxiing and then contact that pad on a discrete frequency to be assigned a lane. You usually deice with engines running at deice pads.