Thursday, March 30, 2006

The Grand Plan

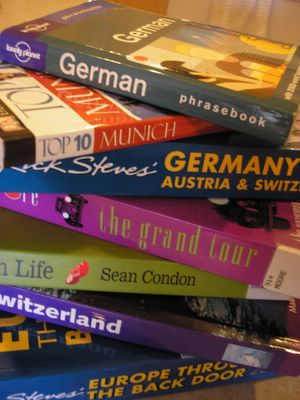

I'm not sure if I've mentioned it here before, but this summer Dawn and I are going to Switzerland, Austria, and southern Germany for several weeks. I've been doing a lot of planning for it lately - not because I want an immaculately planned vacation, but because I enjoy the process, and because while planning I learn a lot about where we're going, which gets me more excited to go.

Hiking is the focus of this trip, and most of it will be in the Alps. We actually meant to take this trip last year, but we bought our house instead. We've been saving for the trip since, and now it looks like it's a go for mid-July.

Of course, that's a pretty ugly time to non-rev to Europe. We're just going to buy a ton of backup passes on Swiss, Lufthansa, Northwest, American, British Airways, and Virgin Atlantic. Between all those carriers, and giving ourselves several days for travel, I think we'll manage to get ourselves to Zürich, perhaps via London, Amsterdam, or Frankfurt. Once we're in Switzerland, we'll be using rail passes to get around, and then renting a car for our short stays in Austria and Germany.

After Zürich, we'll be touring Bern and Luzern, before catching a train across the St Gothard Pass and down the Rhône river valley to Zermatt, near the Matterhorn. There, we'll make overnight hikes to the Schönbielhütte mountain hut and Fluhalp berggasthaus. After Zermatt, we'll stop for a night in Interlaken before pressing into the Jungfrau region. We'll be staying at least four nights at the Mountain Hostel in the small village of Gimmelwald, and taking day hikes from there.

After Gimmelwald, we're renting a car in Luzern and driving to Reutte, Austria. Reutte is just across the German border from the more well-known towns of Füssen and Oberammergau, making it ideal as a base to explore "Mad King" Ludwig II's castles (Neuschwanstein, Hohenschwangau, and Linderhof) as well as the ruined castles of Ehrenberg near Reutte itself. We'll be staying in a privatzimmer in Reutte; many people rent spare rooms for around €30/night.

Our last stop will be Munich. Besides the "Hofbräuhaus and Schloss Schleißheim" type stuff, we'll try to get out to the Andechs monastary and Dachau concentration camp - I've wanted to visit Dachau in particular for a long time. After that it'll be time to play the nonrev lotto once more. If it takes a while to get out, oh well - there are worse places to be stuck than Munich.

So there you have it - everything you need to stalk Dawn and I on our trip this summer. If any of you have been to the aforementioned places and have any good stories and/or tips, I'd love to hear'em.

Wednesday, March 29, 2006

Tuesday, March 28, 2006

Playing Catchup

I'm ashamed to report that I haven't looked at any of the blogs on my blogroll in several weeks. I dunno how I suddenly got so busy, but between working on a project for the union, planning our European trip this summer, and work, I haven't had a whole lot of time to write here, much less keep up with others in the aviation blogosphere. Too bad, I've been missing some good stuff.

Over at RantAir, GC's been posting some humorous QRH and Immediate Action card knockoffs. If you're at work you might want to hold off, as some of them contain some salty language. The "GPWS Flowchart" , a classic bit of cockpit humor, is more suitable for work viewing.

Very big congratulations are in order to the one and only Aviatrix of Cockpit Conversation - she got that job she's been after, with "Vole Airlines." And, she's flying an airplane that's near and dear to my heart, the "Weedwhacker." I have a few hundred hours flying boxes around in Weedwhackers and they're well-designed, well-built, and fun to fly airplanes. Congrats Trixie!

Dave at Flight Level 390 had a very cool encounter with a WWII veteran who served as a ball turret gunner in the B-17. With every passing year, we lose more and more of the fine men and women who won that war; every meeting becomes more precious, an increasingly rare chance to learn about that part of history from someone who was there.

Everybody's favorite Freight Dog, John, is heading to the sim and has some related throughts on the subject of training. My current airline used to require its pilots to memorize lots of useless trivia ("How many rivets are there on the side of the cowling?") but is now much better about prioritizing "need to know" stuff versus "nice to know" stuff.

Ron Rapp posts some interesting comments related to a loss of pitch control incident that happened to American Eagle a few years back. Remember my last sim session? The point of the unlikely-but-possible scenarios was to show that at some point the checklist is inadequate; once you're at that point, you need to throw the book out the window and use your knowledge and skill to figure out a solution to save the airplane. The situation Ron talks about is another scenario we run in the sim at my company.

Much of the country has experienced some pretty nice weather over the last few weeks, but winter flying isn't completely over for the season. Captain Wilko writes about a training mission in which he found himself in an uncomfortable encounter with ice and turbulence over the mountains. The real danger of this story is that he came out okay, and it's going to be easier to push it next time. I think he's learned the proper lesson, though.

Last but certainly not least, I can never get enough of Shawn Roberts' beautiful pictures. Keep it up, Shawn!

Good stuff, everybody. You've kept me entertained tonight.

Over at RantAir, GC's been posting some humorous QRH and Immediate Action card knockoffs. If you're at work you might want to hold off, as some of them contain some salty language. The "GPWS Flowchart" , a classic bit of cockpit humor, is more suitable for work viewing.

Very big congratulations are in order to the one and only Aviatrix of Cockpit Conversation - she got that job she's been after, with "Vole Airlines." And, she's flying an airplane that's near and dear to my heart, the "Weedwhacker." I have a few hundred hours flying boxes around in Weedwhackers and they're well-designed, well-built, and fun to fly airplanes. Congrats Trixie!

Dave at Flight Level 390 had a very cool encounter with a WWII veteran who served as a ball turret gunner in the B-17. With every passing year, we lose more and more of the fine men and women who won that war; every meeting becomes more precious, an increasingly rare chance to learn about that part of history from someone who was there.

Everybody's favorite Freight Dog, John, is heading to the sim and has some related throughts on the subject of training. My current airline used to require its pilots to memorize lots of useless trivia ("How many rivets are there on the side of the cowling?") but is now much better about prioritizing "need to know" stuff versus "nice to know" stuff.

Ron Rapp posts some interesting comments related to a loss of pitch control incident that happened to American Eagle a few years back. Remember my last sim session? The point of the unlikely-but-possible scenarios was to show that at some point the checklist is inadequate; once you're at that point, you need to throw the book out the window and use your knowledge and skill to figure out a solution to save the airplane. The situation Ron talks about is another scenario we run in the sim at my company.

Much of the country has experienced some pretty nice weather over the last few weeks, but winter flying isn't completely over for the season. Captain Wilko writes about a training mission in which he found himself in an uncomfortable encounter with ice and turbulence over the mountains. The real danger of this story is that he came out okay, and it's going to be easier to push it next time. I think he's learned the proper lesson, though.

Last but certainly not least, I can never get enough of Shawn Roberts' beautiful pictures. Keep it up, Shawn!

Good stuff, everybody. You've kept me entertained tonight.

Saturday, March 25, 2006

Friday, March 24, 2006

Thursday, March 23, 2006

And So It Begins

The pilots at my airline are working under a contract that was signed in September 2001 and becomes amendable this coming September. Under the Railway Labor Act, which governs labor relations at unionized airlines, either party can request that an opening to contract negotiations six months before the amendable date. As expected, our management delivered that letter to the union this week.

The company decided to use the letter as an opening salvo in the PR war by posting it to the employee website. Not content to simply comply with the law by requesting negotiations, the letter attempts to frame negotiations in the company's favor. More or less, they're claiming that they gave away the shop with the last contract, plus everyone else's labor costs have decreased, therefore in keeping with their "compensation philosophy," pilot costs must decrease. This was backed up by graph after graph comparing our payrates to the likes of Mesa and Chautauqua.

A word to management: The airline is doing well. Do you really think we're going to bend our expectations to suit your "compensation philosophy" so the shareholders can pocket a few more cents per share while our first officers go on food stamps? Get freaking real. Our pilot group is dead set against any concessionary contract, and compared to five years ago our leadership is more experienced, our communications improved, and our unity impressive. You do not get to set the framework for these negotiations, clumsy propaganda attempts notwithstanding.

This is the first time I've written about our negotiations, and it will probably be the last time until we've signed the (non-concessionary!) contract. It's a subject that's typically kept fairly quiet from the public until the union decides to make their case. When they do, my union speaks for me. If management is reading this blog, they don't need to hear my take - once again, my union leadership speaks for me. Once the contract is signed - perhaps some time from now - I'll write freely about it.

For what it's worth, I recently began volunteering for our union's communications committee. I'm tired of seeing this profession dragged down into the mud. It's worth fighting for.

The company decided to use the letter as an opening salvo in the PR war by posting it to the employee website. Not content to simply comply with the law by requesting negotiations, the letter attempts to frame negotiations in the company's favor. More or less, they're claiming that they gave away the shop with the last contract, plus everyone else's labor costs have decreased, therefore in keeping with their "compensation philosophy," pilot costs must decrease. This was backed up by graph after graph comparing our payrates to the likes of Mesa and Chautauqua.

A word to management: The airline is doing well. Do you really think we're going to bend our expectations to suit your "compensation philosophy" so the shareholders can pocket a few more cents per share while our first officers go on food stamps? Get freaking real. Our pilot group is dead set against any concessionary contract, and compared to five years ago our leadership is more experienced, our communications improved, and our unity impressive. You do not get to set the framework for these negotiations, clumsy propaganda attempts notwithstanding.

This is the first time I've written about our negotiations, and it will probably be the last time until we've signed the (non-concessionary!) contract. It's a subject that's typically kept fairly quiet from the public until the union decides to make their case. When they do, my union speaks for me. If management is reading this blog, they don't need to hear my take - once again, my union leadership speaks for me. Once the contract is signed - perhaps some time from now - I'll write freely about it.

For what it's worth, I recently began volunteering for our union's communications committee. I'm tired of seeing this profession dragged down into the mud. It's worth fighting for.

Wednesday, March 22, 2006

The Poor Pilot's Guide to Cheap Living

Congratulations! After years of working hard getting your ratings, flight instructing, and flying boxes, you finally got the magic call you'd been waiting for. You're now cruising the flight levels in comfort and style - and earning $19 per hour to do so. The money will improve once you upgrade, but unfortunately your company just lost a major contract to another regional that pays their newhires $18 per hour. Now you're running the numbers and they don't look good: you're facing a long period of low pay, your expenses are outstripping your $1500/month income, and your savings account from pre-aviation life is just about depleted.

Welcome to aviation, my friend. Many a pilot has been exactly where you are today. If you look at the senior captains of your company, you'll see behavioral patterns that betray their former life of poverty. The appetite for free crew meals, stealing newspapers from the departure lounge to avoid buying one, driving a 1987 Chevette to work: all signs of a learned cheapness forced upon every pilot who has been in this industry for long. Don't scoff at these guys - they are the standard you should aspire to! I've compiled some of the best tips on living miserly to accompany my last post about cheap eats on the road.

Homelessness: Not Just For Homeless People!

Think of how much you pay every month for that apartment of yours. It's probably your biggest expense, yet it sits empty a lot of the time while you're off on trips. Do you really need it? Sure, it's nice to have your own place, but if you're young and single it's often an unneccessary expense. There are lots of warm, cozy overpasses and cardboard boxes to be had in your city. OK, I won't go that far, we should establish safe and clean as minimum criteria in our quest for the cheapest lodging. But there are many ways you can get a roof over your head without shelling out 2/3 of your monthly earnings.

Couch-Surfing

I actually did this when I was flight instructing in LA; I literally lived on somebody's couch. In my case, it was an apartment shared at any one time by 6 to 8 other flight instructors and full-time students. I paid $100/mo to sleep on the couch while everyone else was paying $200 for a mattress. Suckers! If you can find an apartment full of similarly broke people, you can probably talk them into a deal like this. The local flight school is a great place to start.

Crashpadding It

Most airline domiciles have crashpads nearby. A crashpad is an apartment, condo, or house that is used by commuting crewmembers when they need to spend a night at their base due to an early showtime or late release time. They pay a small amount, often under $100/month, to use a bed whenever they're in town. There are often more renters than there are beds, and people are always coming and going. Many crashpads will also rent to a limited number of full-timers, usually for $200-300/month. I did this during my internship in St. Louis. You get to meet lots of cool people and there's always something interesting going on. The bad news is that on an exceptionally full night, you may come home to find all beds taken. See: couch-surfing!

Look for crashpad listings on your local crew room bulletin board. If you're a flight instructor or box hauler, crashpads may still take you, but you'll need an airline pilot buddy to find some listings for you, as they're not typically seen outside crew rooms.

Renting a Room

An alternative to crashpadding is to rent a room from a normal person (ie non-aviation). It won't be as cheap as crashpadding, but it won't be as crazy either. You'll probably pay half or less of what you're paying for an apartment now. Check your Sunday classified listings.

Living in a van down by the river!

I'm not kidding; this is my serious face. I've known pilots that literally live out of their vehicles. One was a flight instructor in Grand Forks; another was a full-time student in LA; the other was a pilot for Ameriflight in Burbank. What all of these guys had in common was owning spacious vans or RVs and having facilities (showers, kitchens, lounges) available to them nearby. I'm not sure how the Grand Forks guy survived the winters...I think he may have actually slept in the flight instructor lounge and just used his VW van as a wardrobe/locker. It's more extreme than I'd go, but I can't help but admire the guy.

Get Some Roomies

So maybe you want to keep your current apartment, or you own your place. Either way, you can help make the rent/mortgage payments by bringing in a few roomies. When my friend Kelly was hired as a mechanic at my airline, she rented our basement the first few months she was out here, and it was really ideal. Renting out rooms does work best when you know or work with the people who move in. That's not to say that strangers are neccessarily trouble, but you just don't know, and it's a different situation than renting from strangers because now you're responsible for the place. I'd suggest posting a flying on the crew room or flight school bulletin board.

An alternative is to set up your place as a crashpad. If you're fairly social and don't mind people always coming and going, you could get enough crashpadders to pay your rent or mortgage. You will have to spend some money at the outset for additional furniture, particularly beds and mattresses.

Commuting

Normally I advise pilots against commuting. It adds a whole lot of hassle to your life and sucks away your free time. But, if you're based in a very expensive locale, moving to a cheaper town may justify commuting. Here's the key: there should be lots of flights between the two towns, either on your carrier or one that has a jumpseat agreement with you.

Keep in mind that you'll still be spending some nights in your base city due to early showtimes and late releases. Consider whether you'll need a crashpad or hotel, and factor that expense into your decision. If you have friends or family in your base city, see whether you'd be able to crash on their couch a few times a month. I know some commuters that use our crew lounges as crashpads. Comfortable recliners, cable TV, free vending machine food - what more could a pilot want?

Bid the Worst Lines

Some people value their free time. I certainly do. Others contend that free time is simply when you're spending money instead of making it. Every airline has some really nasty lines that go super junior every month, sometimes even below reserve lines. These typically have the worst days off and trips with a ton of flying. Between the extra hours and all the tax-free per diem, you can make a lot of money. Of course, living on the road all the time can be expensive, but it won't be if you read my last post. Also, some of the gnarlier lodging arrangements (like sleeping on couches or crashpadding) are a lot more bearable if you're not home very often.

Travel a lot

This one is pretty counter-intuitive. Most people think that traveling is a luxury that adds expense. If you're smart, though, it can actually save you money. Traveling as a jumpseater is typically free, and on major airlines you may get free food as well. I've known pilots who jumpseated for the food alone. I've even heard of pilots jumpseating on transcontinental redeyes to avoid paying for a hotel, then turning right back around on the westbound morning flight for free breakfast. When I was an intern at TWA, I once jumpseated to Miami in the morning (free breakfast!), took the bus to South Beach ($2!), sat on the beach all day (free!), and jumpseated back at night (free dinner!). A widespread network of friends can make traveling even cheaper.

Mooch off friends and family

If you have enough friends and family scattered all over the place, you could spend so little time at your base that you can just get a crashpad at the "commuter's rate" (often under $100). Your grandparents in Florida, your high school buddy in New York, your aunt in Texas, your long lost pen-pal in Nebraska, and your sister's boyfriend's second cousin in Missoula would all love to have you visit and sleep on their couch and eat their food.

Ditch the Car (or trade down)

Like the apartment, your car sits unused a good portion of the time. Between aquisition costs, insurance, fuel, and maintenance, it can be a major expense. Do you really need it? The U.S. is nowhere near Europe in efficient mass transportation, but it's becoming increasingly common to see airports served by light rail connections. Would you be able to ride the train to work? Many airline workers get very cheap monthly or annual passes. Here in Portland, airline employees can ride the MAX for $40/year. Think how much that'd save over a car.

There are many cities where this just isn't practical (I can hear the Angelenos laughing!). But I'll bet you could save some serious money by trading down to a beater. Sitting in the weather in employee lots for four days at a time is hell on cars anyways, you don't want to do that to a nice car. I drove a 1994 Buick LeSabre for years. Everybody laughed at the "Grandpamobile," but it drove nice, got good mileage, had low insurance rates, and was easy to work on myself.

Final Cost-Slashing Suggestions

- Consider cutting entertainment items like cable TV and even internet access. Broadcast TV isn't that much worse than cable (it's all relative!) and you can get your daily Blogging at FL250 fix by mooching off an unsecured wifi hotspot. You could also get internet access at the library (I hear you can check out books there for free, too).

- Salvation Army, Ebay, Craigslist, garage sales. One man's junk is a broke pilot's treasure.

- Find fun free stuff to do in your spare time. Examples: surfing, swimming, hiking, backcountry camping, snowshoeing, rollerblading, Code Pink rallies, clubbing baby seals, russian roullette, etc.

- Student loans can wait. The interest rates are low, particularly on federally subsidized loans, so defer, defer, defer. Even if you don't technically meet the deferment criteria, you can usually work out something with your lender. I mean, what are they gonna do to collect the loan, take your car? Not if you're driving that Chevette!

*****

The key to surviving these early years is not to just tolerate poverty, but embrace it. Accept the fact that you're one broke dude/chick, and stop trying to live a lifestyle that pretends you're not. Make it your personal challenge to be as wretchedly cheap as any pilot that ever lived. Not only will you survive and prosper in your early years, but you'll be able to wear your cheapness as a badge of honor for the rest of your career. You'll proudly share your favorite cheapo tricks to new pilots, and the cycle will be complete.

Welcome to aviation, my friend. Many a pilot has been exactly where you are today. If you look at the senior captains of your company, you'll see behavioral patterns that betray their former life of poverty. The appetite for free crew meals, stealing newspapers from the departure lounge to avoid buying one, driving a 1987 Chevette to work: all signs of a learned cheapness forced upon every pilot who has been in this industry for long. Don't scoff at these guys - they are the standard you should aspire to! I've compiled some of the best tips on living miserly to accompany my last post about cheap eats on the road.

Homelessness: Not Just For Homeless People!

Think of how much you pay every month for that apartment of yours. It's probably your biggest expense, yet it sits empty a lot of the time while you're off on trips. Do you really need it? Sure, it's nice to have your own place, but if you're young and single it's often an unneccessary expense. There are lots of warm, cozy overpasses and cardboard boxes to be had in your city. OK, I won't go that far, we should establish safe and clean as minimum criteria in our quest for the cheapest lodging. But there are many ways you can get a roof over your head without shelling out 2/3 of your monthly earnings.

Couch-Surfing

I actually did this when I was flight instructing in LA; I literally lived on somebody's couch. In my case, it was an apartment shared at any one time by 6 to 8 other flight instructors and full-time students. I paid $100/mo to sleep on the couch while everyone else was paying $200 for a mattress. Suckers! If you can find an apartment full of similarly broke people, you can probably talk them into a deal like this. The local flight school is a great place to start.

Crashpadding It

Most airline domiciles have crashpads nearby. A crashpad is an apartment, condo, or house that is used by commuting crewmembers when they need to spend a night at their base due to an early showtime or late release time. They pay a small amount, often under $100/month, to use a bed whenever they're in town. There are often more renters than there are beds, and people are always coming and going. Many crashpads will also rent to a limited number of full-timers, usually for $200-300/month. I did this during my internship in St. Louis. You get to meet lots of cool people and there's always something interesting going on. The bad news is that on an exceptionally full night, you may come home to find all beds taken. See: couch-surfing!

Look for crashpad listings on your local crew room bulletin board. If you're a flight instructor or box hauler, crashpads may still take you, but you'll need an airline pilot buddy to find some listings for you, as they're not typically seen outside crew rooms.

Renting a Room

An alternative to crashpadding is to rent a room from a normal person (ie non-aviation). It won't be as cheap as crashpadding, but it won't be as crazy either. You'll probably pay half or less of what you're paying for an apartment now. Check your Sunday classified listings.

Living in a van down by the river!

I'm not kidding; this is my serious face. I've known pilots that literally live out of their vehicles. One was a flight instructor in Grand Forks; another was a full-time student in LA; the other was a pilot for Ameriflight in Burbank. What all of these guys had in common was owning spacious vans or RVs and having facilities (showers, kitchens, lounges) available to them nearby. I'm not sure how the Grand Forks guy survived the winters...I think he may have actually slept in the flight instructor lounge and just used his VW van as a wardrobe/locker. It's more extreme than I'd go, but I can't help but admire the guy.

Get Some Roomies

So maybe you want to keep your current apartment, or you own your place. Either way, you can help make the rent/mortgage payments by bringing in a few roomies. When my friend Kelly was hired as a mechanic at my airline, she rented our basement the first few months she was out here, and it was really ideal. Renting out rooms does work best when you know or work with the people who move in. That's not to say that strangers are neccessarily trouble, but you just don't know, and it's a different situation than renting from strangers because now you're responsible for the place. I'd suggest posting a flying on the crew room or flight school bulletin board.

An alternative is to set up your place as a crashpad. If you're fairly social and don't mind people always coming and going, you could get enough crashpadders to pay your rent or mortgage. You will have to spend some money at the outset for additional furniture, particularly beds and mattresses.

Commuting

Normally I advise pilots against commuting. It adds a whole lot of hassle to your life and sucks away your free time. But, if you're based in a very expensive locale, moving to a cheaper town may justify commuting. Here's the key: there should be lots of flights between the two towns, either on your carrier or one that has a jumpseat agreement with you.

Keep in mind that you'll still be spending some nights in your base city due to early showtimes and late releases. Consider whether you'll need a crashpad or hotel, and factor that expense into your decision. If you have friends or family in your base city, see whether you'd be able to crash on their couch a few times a month. I know some commuters that use our crew lounges as crashpads. Comfortable recliners, cable TV, free vending machine food - what more could a pilot want?

Bid the Worst Lines

Some people value their free time. I certainly do. Others contend that free time is simply when you're spending money instead of making it. Every airline has some really nasty lines that go super junior every month, sometimes even below reserve lines. These typically have the worst days off and trips with a ton of flying. Between the extra hours and all the tax-free per diem, you can make a lot of money. Of course, living on the road all the time can be expensive, but it won't be if you read my last post. Also, some of the gnarlier lodging arrangements (like sleeping on couches or crashpadding) are a lot more bearable if you're not home very often.

Travel a lot

This one is pretty counter-intuitive. Most people think that traveling is a luxury that adds expense. If you're smart, though, it can actually save you money. Traveling as a jumpseater is typically free, and on major airlines you may get free food as well. I've known pilots who jumpseated for the food alone. I've even heard of pilots jumpseating on transcontinental redeyes to avoid paying for a hotel, then turning right back around on the westbound morning flight for free breakfast. When I was an intern at TWA, I once jumpseated to Miami in the morning (free breakfast!), took the bus to South Beach ($2!), sat on the beach all day (free!), and jumpseated back at night (free dinner!). A widespread network of friends can make traveling even cheaper.

Mooch off friends and family

If you have enough friends and family scattered all over the place, you could spend so little time at your base that you can just get a crashpad at the "commuter's rate" (often under $100). Your grandparents in Florida, your high school buddy in New York, your aunt in Texas, your long lost pen-pal in Nebraska, and your sister's boyfriend's second cousin in Missoula would all love to have you visit and sleep on their couch and eat their food.

Ditch the Car (or trade down)

Like the apartment, your car sits unused a good portion of the time. Between aquisition costs, insurance, fuel, and maintenance, it can be a major expense. Do you really need it? The U.S. is nowhere near Europe in efficient mass transportation, but it's becoming increasingly common to see airports served by light rail connections. Would you be able to ride the train to work? Many airline workers get very cheap monthly or annual passes. Here in Portland, airline employees can ride the MAX for $40/year. Think how much that'd save over a car.

There are many cities where this just isn't practical (I can hear the Angelenos laughing!). But I'll bet you could save some serious money by trading down to a beater. Sitting in the weather in employee lots for four days at a time is hell on cars anyways, you don't want to do that to a nice car. I drove a 1994 Buick LeSabre for years. Everybody laughed at the "Grandpamobile," but it drove nice, got good mileage, had low insurance rates, and was easy to work on myself.

Final Cost-Slashing Suggestions

- Consider cutting entertainment items like cable TV and even internet access. Broadcast TV isn't that much worse than cable (it's all relative!) and you can get your daily Blogging at FL250 fix by mooching off an unsecured wifi hotspot. You could also get internet access at the library (I hear you can check out books there for free, too).

- Salvation Army, Ebay, Craigslist, garage sales. One man's junk is a broke pilot's treasure.

- Find fun free stuff to do in your spare time. Examples: surfing, swimming, hiking, backcountry camping, snowshoeing, rollerblading, Code Pink rallies, clubbing baby seals, russian roullette, etc.

- Student loans can wait. The interest rates are low, particularly on federally subsidized loans, so defer, defer, defer. Even if you don't technically meet the deferment criteria, you can usually work out something with your lender. I mean, what are they gonna do to collect the loan, take your car? Not if you're driving that Chevette!

*****

The key to surviving these early years is not to just tolerate poverty, but embrace it. Accept the fact that you're one broke dude/chick, and stop trying to live a lifestyle that pretends you're not. Make it your personal challenge to be as wretchedly cheap as any pilot that ever lived. Not only will you survive and prosper in your early years, but you'll be able to wear your cheapness as a badge of honor for the rest of your career. You'll proudly share your favorite cheapo tricks to new pilots, and the cycle will be complete.

Tuesday, March 14, 2006

The Starving First Officer's Guide to Dining

So you're a new first officer at a regional airline, struggling to make ends meet. You're also a young, busy person who needs to eat. Unfortunately, not only does your new job pay poorly, it also keeps you on the road four or more nights a week, often in rather expensive cities. It's a struggle to get the nourishment you need without completely starving your malnourished bank account. Take heart, my ravenous gear-throwing three-striper friend: many a pilot has been in your place, and there is a wealth of knowledge on eating cheaply in this profession. Allow me to share some of the best tips.

Learn to choke down crew meals.

I'm not sure if airline food ever was that good, even in the "Golden Age." But whatever palatability crew meals once had is gone forever. These days, you're lucky to find actual crew meals on board any airplane, and it's almost unheard of at the regionals. If your airline is like mine, the "crew meals" come out of vending machines in the crew lounges. The food is what you'd expect from any commercial vending machine, with one crucial difference: it's free! Ignore the taste. Nevermind that it's grossly unhealthy. Pay no attention to that expiration date! All you need to know is that it'll quiet your grumbling tummy and it's free.

At my airline, access to this cornucopia of saturated fats and sugary carbs is gained via a magnetic stripe card. Management keeps track of how often you swipe the card. One of my friends who saw the sheet reports that the top user so far this year, with over 100 swipes in two months, is a 22-year CRJ captain. He's making over $120/hr but he's clung to the eating habits of his youth. Bravo! This man realizes that a 14-hour duty day is a blessing in disguise, an opportunity to get breakfast, lunch, and dinner for free from the bounty of the crew room vending machine.

Savor those Snacks.

Although crew meals have gone the way of the dodo bird, the DC-8, and $200/hr captain payrates, there is still some food left on our airplanes. If you don't like peanuts, you can root around a bit to find yourself some chex mix or potato chips. If you have a long day in between crew lounges with free food, this can keep you going without resorting to (gasp) buying food.

Know Thy Discounts (at the airport).

Put your hat back on and take that Old Navy fleece pullover off, because that adorable little uniform is your ticket to savings at your local airport's eateries. When you're far from the nearest free Mr. Rib and you can't choke down one more peanut, employee discounts make overpriced airport fare a little easier on the cash. They range between 10%-30% off regular prices, so make it your personal mission to know the best deals at every airport you fly to. You can even find some freebies. When Anthony's Restaurant and Fish Bar first opened at Sea-Tac, they offered a free coffee and cup of clam chowder to any crewmember in uniform...and it drove them to the brink of bankruptcy in their very first month. I think I still have some of that chowder in storage...

Back to Basics.

Even without employee discounts, some airport restaurants offer great deals on basic a la carte items. You can get a big rice and beans plate from Maui Tacos in Boise for $1.79. It used to be a buck, but they raised the price to keep the horde of pilots from overrunning the place. It's still a good deal - you go to their salsa bar, mix in a little pico de gallo, top it off with some pineapple-chipolte sauce, and you have yourself a finger-lickin' meal for under $2. It'll also provide hours of entertainment as you and the captain lob bean-fueled stench bombs at each other across the cockpit.

Fear No Grease.

Another budget option at the airport food court is the local installment of McDonalds or other fast food joint. Sure, Morgan Spurlock was sick and fat and gross at the end of Super Size Me, but I'll bet he still coulda flown a CRJ! These options are also great for intra-cockpit fart wars.

Know thy Discounts (at the hotel.)

Hotel restaurants serve uninspired fare at price markups similar to airport restaurants, but your airline badge may be just the ticket for uninspired fare at 30% off. Hotels that have lots of airline crew running around tend to give them some decent discounts on food and sometimes even drink. This is particularly handy for the 9-hour overnights in Butte in the dead of winter. You sure as heck don't want to go scrounging for cheap food outside.

Brown Bag It.

What's that you say? You want something cheap and healthy? Pbbttth, the solar radiation will probably have you dying of cancer by age 60 anyways. But, to improve your chances of surviving into dotage, here's an option: pack your own lunch. You can pack fruits and salads and whole-grain sandwiches, fresh from your own refrigerator. You'll need a big insulated lunch bag and some industrial-sized ice packs. Even then, you may not be able to pack for an entire four day trip. Still, your first few days will be yummy and (more importantly) cheap. If you have a Canadian layover, be aware that customs officials might confiscate your food. They'd rather you take your chances with Mad Cow Disease in the local beef.

Back to College!

As an alternative to lugging around a lunch pail along with your overnight bag and flight kit and laptop bag, you can throw a few packs of ramen in your overnight bag. It got you through college, it can get you through your regional years! You just need to scrape together $10 to buy a pallet at Costco, after that it gets cheap.

Raid the Supermarket.

You don't neccessarily need to bring your dinner with you, since most layover hotels tend to be surrounded by the various trappings of american civilization, including the cavernous supermarket. Buying a whole loaf of bread with a cheese wheel and a half of ham might be going overboard, but you can usually find relatively healthy fresh sandwiches in the deli section. Save $.10 with your Ralph's card!!!

Free Food Makes Happy Hour Happy.

Don't forget, many hotel bars (and bars in general) have free or very cheap food during happy hour (generally weekdays 4pm-6pm). At our Sacramento layover, we get $1 domestic beer and $2 microbrews. I usually spring for a tasty Pyramid Hefeweizen and snack on free buffalo wings and potstickers while I visit with other crewmembers feasting for free. Half the time a Southwest guy buys my second beer. I've yet to have a United pilot do so, but I think a lot of those guys are in the same financial boat as me since management has raped and pillaged their way through UA payrates and pensions.

Suck from the public teat.

A number of our layover hotels are located in, umm, underprivledged areas. The bad news is you have to worry about being mugged. The good news is that a soup kitchen is sure to be nearby! Just make yourself look as pathetic as possible, which shouldn't be too hard after a 14 hour duty day with 8 hours of flying. I've never done this myself, but I know pilots who have. I think we can say pretty definitively that they're going to hell, but they'll go with a little more cash in their pockets!

Rumage through the nearest dumpster.

Ok, I've never done this and have never seen nor heard of a pilot who has. But it would sure make a hilarious staged photo! The first person to take a picture of themself, in uniform (hat required for pilots!), rumaging for food in a dumpster, gets a free meal on me. You can get anything you want off the dollar menu at McDonalds!

***

Following these tips, you should be able to survive those years flying for a regional airline. Don't worry too much about lacking the time or money to eat properly. Before you know it, you'll be a senior captain, and the only memory of these years will be your 50 extra pounds and an early heart attack!

Learn to choke down crew meals.

I'm not sure if airline food ever was that good, even in the "Golden Age." But whatever palatability crew meals once had is gone forever. These days, you're lucky to find actual crew meals on board any airplane, and it's almost unheard of at the regionals. If your airline is like mine, the "crew meals" come out of vending machines in the crew lounges. The food is what you'd expect from any commercial vending machine, with one crucial difference: it's free! Ignore the taste. Nevermind that it's grossly unhealthy. Pay no attention to that expiration date! All you need to know is that it'll quiet your grumbling tummy and it's free.

At my airline, access to this cornucopia of saturated fats and sugary carbs is gained via a magnetic stripe card. Management keeps track of how often you swipe the card. One of my friends who saw the sheet reports that the top user so far this year, with over 100 swipes in two months, is a 22-year CRJ captain. He's making over $120/hr but he's clung to the eating habits of his youth. Bravo! This man realizes that a 14-hour duty day is a blessing in disguise, an opportunity to get breakfast, lunch, and dinner for free from the bounty of the crew room vending machine.

Savor those Snacks.

Although crew meals have gone the way of the dodo bird, the DC-8, and $200/hr captain payrates, there is still some food left on our airplanes. If you don't like peanuts, you can root around a bit to find yourself some chex mix or potato chips. If you have a long day in between crew lounges with free food, this can keep you going without resorting to (gasp) buying food.

Know Thy Discounts (at the airport).

Put your hat back on and take that Old Navy fleece pullover off, because that adorable little uniform is your ticket to savings at your local airport's eateries. When you're far from the nearest free Mr. Rib and you can't choke down one more peanut, employee discounts make overpriced airport fare a little easier on the cash. They range between 10%-30% off regular prices, so make it your personal mission to know the best deals at every airport you fly to. You can even find some freebies. When Anthony's Restaurant and Fish Bar first opened at Sea-Tac, they offered a free coffee and cup of clam chowder to any crewmember in uniform...and it drove them to the brink of bankruptcy in their very first month. I think I still have some of that chowder in storage...

Back to Basics.

Even without employee discounts, some airport restaurants offer great deals on basic a la carte items. You can get a big rice and beans plate from Maui Tacos in Boise for $1.79. It used to be a buck, but they raised the price to keep the horde of pilots from overrunning the place. It's still a good deal - you go to their salsa bar, mix in a little pico de gallo, top it off with some pineapple-chipolte sauce, and you have yourself a finger-lickin' meal for under $2. It'll also provide hours of entertainment as you and the captain lob bean-fueled stench bombs at each other across the cockpit.

Fear No Grease.

Another budget option at the airport food court is the local installment of McDonalds or other fast food joint. Sure, Morgan Spurlock was sick and fat and gross at the end of Super Size Me, but I'll bet he still coulda flown a CRJ! These options are also great for intra-cockpit fart wars.

Know thy Discounts (at the hotel.)

Hotel restaurants serve uninspired fare at price markups similar to airport restaurants, but your airline badge may be just the ticket for uninspired fare at 30% off. Hotels that have lots of airline crew running around tend to give them some decent discounts on food and sometimes even drink. This is particularly handy for the 9-hour overnights in Butte in the dead of winter. You sure as heck don't want to go scrounging for cheap food outside.

Brown Bag It.

What's that you say? You want something cheap and healthy? Pbbttth, the solar radiation will probably have you dying of cancer by age 60 anyways. But, to improve your chances of surviving into dotage, here's an option: pack your own lunch. You can pack fruits and salads and whole-grain sandwiches, fresh from your own refrigerator. You'll need a big insulated lunch bag and some industrial-sized ice packs. Even then, you may not be able to pack for an entire four day trip. Still, your first few days will be yummy and (more importantly) cheap. If you have a Canadian layover, be aware that customs officials might confiscate your food. They'd rather you take your chances with Mad Cow Disease in the local beef.

Back to College!

As an alternative to lugging around a lunch pail along with your overnight bag and flight kit and laptop bag, you can throw a few packs of ramen in your overnight bag. It got you through college, it can get you through your regional years! You just need to scrape together $10 to buy a pallet at Costco, after that it gets cheap.

Raid the Supermarket.

You don't neccessarily need to bring your dinner with you, since most layover hotels tend to be surrounded by the various trappings of american civilization, including the cavernous supermarket. Buying a whole loaf of bread with a cheese wheel and a half of ham might be going overboard, but you can usually find relatively healthy fresh sandwiches in the deli section. Save $.10 with your Ralph's card!!!

Free Food Makes Happy Hour Happy.

Don't forget, many hotel bars (and bars in general) have free or very cheap food during happy hour (generally weekdays 4pm-6pm). At our Sacramento layover, we get $1 domestic beer and $2 microbrews. I usually spring for a tasty Pyramid Hefeweizen and snack on free buffalo wings and potstickers while I visit with other crewmembers feasting for free. Half the time a Southwest guy buys my second beer. I've yet to have a United pilot do so, but I think a lot of those guys are in the same financial boat as me since management has raped and pillaged their way through UA payrates and pensions.

Suck from the public teat.

A number of our layover hotels are located in, umm, underprivledged areas. The bad news is you have to worry about being mugged. The good news is that a soup kitchen is sure to be nearby! Just make yourself look as pathetic as possible, which shouldn't be too hard after a 14 hour duty day with 8 hours of flying. I've never done this myself, but I know pilots who have. I think we can say pretty definitively that they're going to hell, but they'll go with a little more cash in their pockets!

Rumage through the nearest dumpster.

Ok, I've never done this and have never seen nor heard of a pilot who has. But it would sure make a hilarious staged photo! The first person to take a picture of themself, in uniform (hat required for pilots!), rumaging for food in a dumpster, gets a free meal on me. You can get anything you want off the dollar menu at McDonalds!

***

Following these tips, you should be able to survive those years flying for a regional airline. Don't worry too much about lacking the time or money to eat properly. Before you know it, you'll be a senior captain, and the only memory of these years will be your 50 extra pounds and an early heart attack!

Saturday, March 11, 2006

I'm google-worthy!

A buddy emailed today to inform me that Blogging at FL250 is the #1 hit for googling "International Jumpseat."

Heh, cool.

Heh, cool.

Thursday, March 09, 2006

Day 4 of a 4-day Trip

14 hours duty time...

7 hours flight time...

7 legs across the Cascades during a Pacific storm...

6 instrument approaches...

3 Flaps 15 landings in gusty crosswinds...

1 approach to minimums to a snow-covered runway in a blizzard...

1 call from crew sked (which turned a 5-leg day into a 7-leg day)...

No end-of-day beer tasted quite as good as last night's.

7 hours flight time...

7 legs across the Cascades during a Pacific storm...

6 instrument approaches...

3 Flaps 15 landings in gusty crosswinds...

1 approach to minimums to a snow-covered runway in a blizzard...

1 call from crew sked (which turned a 5-leg day into a 7-leg day)...

No end-of-day beer tasted quite as good as last night's.

Monday, March 06, 2006

NWA Pilots have a TA

Northwest Airlines and ALPA negotiators reached a tentative agreement late last week, ending a game of brinksmanship that could've ended in a strike that would've likely resulted in the demise of NW. The TA, which still needs to be reviewed by the Northwest pilots' ExCo and voted on by membership, contains significant concessions, but it's not nearly as bad as it could've been. I think you can chalk that up to the unity that Northwest pilots showed in an overwhelming vote to strike.

For those who haven't been following the story closely, Northwest has been operating under chapter 11 bankruptcy protection since September 15 of last year. Since then, they have been aggressively securing concessions from stakeholders, vendors, and (especially) employees. Even before the bankruptcy, Northwest management had demanded a concessionary contract of their mechanics' union that would've resulted in about half of those employees' jobs being outsourced. The Aircraft Mechanics Fraternal Association (AMFA) struck in August 2005 rather than accept the contract; Northwest has thus far successfully withstood the strike by using replacement workers (ie scabs).

If this precedent wasn't enough leverage against other employee groups, bankruptcy protection provided quite a bit more. Northwest filed several 1113(c) motions which, if approved by the judge, would've allowed management to throw out union contracts and impose their own payrates and wage rules. Using this threat, NW secured concessionary contracts from all employee groups except the pilots and flight attendants. In these two cases, the company was demanding scope changes that would've resulted in 50% (FA's) and 25% (pilots) of the jobs being outsourced. The flight attendants threatened to strike, and the pilots actually took a strike vote that was approved last Tuesday with 92% of the membership voting "yes," despite the fact that all sides recognized a stike would probably finish off Northwest. Under this threat, the flight attendants and the company reached a TA on Wednesday, and the pilots two days thereafter.

The good news is that the worst oursourcing provisions are gone. Northwest was trying to replace all international flight attendants with non-union foreign nationals, and outsource all flying on future DC-9 replacements. Under the TA's, international flying is untouched, and all airframes over 76 seats stay at Northwest mainline. The bad news is that the company can outsource unlimited airframes under 76 seats to any other carrier... Mesa, anyone?

The pilot's TA makes permanent the "temporary" 24% pay cut agreed to last November, but there are no additional payrate cuts (this was on top of a 14% cut in 2004). The maximum monthly credit hour figure was raised to 86 hours, vacation time was reduced, deadhead pay cut in half, sick pay reduced, and other concessions that will be bitter to swallow, but don't seem to be near what the company was originally proposing.

My initial reaction is that this is about as good as the pilots could expect to get under current circumstances, and we should be thankful that the company is keeping 76-100 seat jets in-house. Along with decisions at jetBlue and USAirways to keep the EMB-190 at mainline, it looks like we're finally seeing a limit of outsourcing to regional carriers. On the other hand, the 76-100 seat outsourcing proposal could've been a red herring all along, nothing but a bargaining chip to help the company get the rest of their demands. They certainly made the threat credible by allowing the mechanics to strike over outsourcing.

There is a certain segment of pilots that were hoping the Northwest pilots would strike and "burn it down!" Some of the more militant pilots have argued that concessionary contracts will continue to ravage the profession until somebody puts their foot down and says "no more!" If pilots willingly took Northwest down with them rather than take a concessionary contract, these types argue, it would make management at other airlines far less likely to screw with their pilot groups. I disagree. At the very root of things, today's concessionary environment is possible because there are more qualified pilots out there than jobs. Releasing another several thousand experienced pilots into the job market isn't going to give other pilot groups any more leverage. What NW ALPA chose to do was present a very credible threat of strike, backed up by a 92% yes vote, to force the company to drop the outsourcing provisions that would've stripped the union of any leverage when the airline returns to profitability. If you can keep the jobs, any paycut and work rule change is neccessarily temporary; you can fight for it next time around, when the company doesn't have a bankruptcy court in their corner.

Next up: Delta pilots. "May you live in interesting times," indeed.

For those who haven't been following the story closely, Northwest has been operating under chapter 11 bankruptcy protection since September 15 of last year. Since then, they have been aggressively securing concessions from stakeholders, vendors, and (especially) employees. Even before the bankruptcy, Northwest management had demanded a concessionary contract of their mechanics' union that would've resulted in about half of those employees' jobs being outsourced. The Aircraft Mechanics Fraternal Association (AMFA) struck in August 2005 rather than accept the contract; Northwest has thus far successfully withstood the strike by using replacement workers (ie scabs).

If this precedent wasn't enough leverage against other employee groups, bankruptcy protection provided quite a bit more. Northwest filed several 1113(c) motions which, if approved by the judge, would've allowed management to throw out union contracts and impose their own payrates and wage rules. Using this threat, NW secured concessionary contracts from all employee groups except the pilots and flight attendants. In these two cases, the company was demanding scope changes that would've resulted in 50% (FA's) and 25% (pilots) of the jobs being outsourced. The flight attendants threatened to strike, and the pilots actually took a strike vote that was approved last Tuesday with 92% of the membership voting "yes," despite the fact that all sides recognized a stike would probably finish off Northwest. Under this threat, the flight attendants and the company reached a TA on Wednesday, and the pilots two days thereafter.

The good news is that the worst oursourcing provisions are gone. Northwest was trying to replace all international flight attendants with non-union foreign nationals, and outsource all flying on future DC-9 replacements. Under the TA's, international flying is untouched, and all airframes over 76 seats stay at Northwest mainline. The bad news is that the company can outsource unlimited airframes under 76 seats to any other carrier... Mesa, anyone?

The pilot's TA makes permanent the "temporary" 24% pay cut agreed to last November, but there are no additional payrate cuts (this was on top of a 14% cut in 2004). The maximum monthly credit hour figure was raised to 86 hours, vacation time was reduced, deadhead pay cut in half, sick pay reduced, and other concessions that will be bitter to swallow, but don't seem to be near what the company was originally proposing.

My initial reaction is that this is about as good as the pilots could expect to get under current circumstances, and we should be thankful that the company is keeping 76-100 seat jets in-house. Along with decisions at jetBlue and USAirways to keep the EMB-190 at mainline, it looks like we're finally seeing a limit of outsourcing to regional carriers. On the other hand, the 76-100 seat outsourcing proposal could've been a red herring all along, nothing but a bargaining chip to help the company get the rest of their demands. They certainly made the threat credible by allowing the mechanics to strike over outsourcing.

There is a certain segment of pilots that were hoping the Northwest pilots would strike and "burn it down!" Some of the more militant pilots have argued that concessionary contracts will continue to ravage the profession until somebody puts their foot down and says "no more!" If pilots willingly took Northwest down with them rather than take a concessionary contract, these types argue, it would make management at other airlines far less likely to screw with their pilot groups. I disagree. At the very root of things, today's concessionary environment is possible because there are more qualified pilots out there than jobs. Releasing another several thousand experienced pilots into the job market isn't going to give other pilot groups any more leverage. What NW ALPA chose to do was present a very credible threat of strike, backed up by a 92% yes vote, to force the company to drop the outsourcing provisions that would've stripped the union of any leverage when the airline returns to profitability. If you can keep the jobs, any paycut and work rule change is neccessarily temporary; you can fight for it next time around, when the company doesn't have a bankruptcy court in their corner.

Next up: Delta pilots. "May you live in interesting times," indeed.

Thursday, March 02, 2006

Fly for Free! *

* - Some terms and conditions apply: Must work in the struggling air travel industry as the employee of an airline with an uncertain future. Must find open seats on flights that average 90% full. Must be willing to squeeze between "Chuckie" and "Bruno" in seat 28E. Must be prepared for lengthy sits or even sleeping in strange airport terminals. Must be willing to buy fistfulls of backup passes for international travel.

Ah yes, the wonderful world of non-rev travel. It's one of the biggest perks of working for an airline, and indeed is the only reason many people continue to work in the airlines. Most people outside the airline world aren't familiar with how it works, though.

"Non-rev" is short for non-revenue passenger, but is also used as a verb to describe traveling as a non-rev, i.e. "I'm non-reving to Sydney next week." Non-revs are typically airline employees, parents, spouses, children, and guests. Airline employees traveling on company business aren't considered non-rev, since they are guaranteed a seat. Non-revs travel standby, so they only fly if there's a seat left for them. Once all regular passengers, employees on company business, and revenue standby passengers have boarded, any remaining seats are given to non-revs according to a pre-determined "priority list." A priority list might look like this:

Traveling solely on one's own airline or even close codeshares would be pretty limiting, so most of the world's airlines have worked out pass agreements with each other. We purchase non-rev tickets on these airlines through our own airline's ticket counters. The cost varies with each pass agreement. Many tickets, like on United, are "ID90." This means that you pay 10% of the full walkup fare, which can get pretty expensive. You can often find deals on Expedia or Hotwire that are cheaper than ID90s - for a ticket that's positive space! A number of carriers have a flat service charge, which is usually $30-50 (plus tax) for domestic roundtrip travel, around $60-80 for Hawaii or Mexico, and $120-200 for Europe or Asia. Another type of pass that's becoming increasingly popular, especially with foreign carriers, is ZED (Zonal Employee Discount). The cost of a ZED pass depends on the distance traveled, and is the same price for all airlines that accept it. For example, a segment of 4080-5000 miles costs $60 plus tax. It's much cheaper than ID90's and most service charges, and once fully implemented it'll be much more flexible, since passes will be interchangeable among carriers.

Of course, the tax man will always take his due. When buying non-rev tickets on other airlines, you'll have sales tax, airport use fees, and security fees added on. For international travel, most countries add an exorbitant departure tax - $40-80 is common. You pay this even on your own airline, which usually takes it out of your paycheck.

After purchasing the ticket, you need to research which flights to take. I regularly download current timetables for about 30 airlines on my computer; many employees keep them on their PalmPilots or Blackberries. When direct flights aren't feasible, I'll try to connect through the hub city with the most options. For example, if I was trying to get from Portland to Cleveland, I'd probably connect through Chicago, because then I'd have AA, AS, and UA to Chicago, and AA, UA, and DL to Cleveland. Early morning flights sometimes have lighter loads, but afternoon flights may have seats opened up by misconnecting passengers. Eastbound redeye flights used to be a good option for non-revs but have become very popular the last few years. Fridays and Sundays are very bad days to travel standby; Tuesday and Wednesday are best.

Your next step is to see what the load factors look like. On your own airline or a close codeshare, the company often provides a phone number or website where you can check loads. If it's another carrier, a friend at that airline can be a great resource to check loads for you. No friends? Call the airline's reservations line and identify yourself as a non-rev. Some res agents will give you the exact loads, while others will play coy ("it looks okay." What's that mean!?). It's best to check a day or two before the flight at the soonest. If it's seriously oversold, find something else. If there are a few seats left or it's only slightly oversold, you can still try for it, but come up with a good backup plan or two. If 10% or more of the plane is open, you should be fine unless cancellations screw up your plan.

Before showing up at the airport, you need to list yourself, ie get yourself in the airline's reservation system. At your own airline there's probably a website and/or phone number for this; at other airlines you'll do it through their reservation hotline. Once at the airport, you'll go to the check-in counter or kiosk to check in like a regular passenger. You'll get a pass to get through security. At the gate, the agents will assign remaining seats to non-revs towards the end of the boarding process. Just wait for your name to be called. Be ready to go as soon as it is, or they'll give your seat away to the next non-rev on the priority list.

Whether traveling on your own airline or another, there is a code of conduct for non-revs to follow. First, you're expected to dress up. No sandles, no halter tops, no holey jeans or t-shirts, no sweatpants, no ratty sneakers, certainly no pajamas. In other words, don't dress like 50% of today's passengers. If you want any chance at first class, business casual is a minimum. Secondly, don't be a jerk to the gate agents, even if they're rude to you. Be polite and undemanding, and don't ask about open seats every three minutes. If you don't get on, don't protest. If you do get on, introduce yourself as a non-rev to the flight attendants and let them know where you're sitting if they need your help. Don't consider yourself home free until the cabin door is closed and the plane is pushing back; I've had gate agents run onboard at the last minute to replace me with a paying passenger. When the flight attendants offer you a meal, make sure there's enough for everybody first. And when the flight is over, help the flight attendants clean up if that's one of their duties (ie Southwest, jetBlue, most regional airlines, etc).

These days, the U.S. airlines are flying around with some very full airplanes; how they continue to lose massive amounts of money is beyond me. It makes it pretty tough to be a non-rev. The key is staying flexible. Accept that you're not going to get on all the flights, and have a good backup plan. Buy plenty of backup passes on other airlines; they're all refundable if you don't use them. Leave plenty of time in your plans for travel, and don't be surprised if you spend some significant time waiting in airline terminals. I've even spent the night in a few airports. Usually, though, by monitoring the loads, traveling at non-peak times, and making good backup plans, you can get around with a minimum of fuss.

So you don't work for the airlines, but your sister's friend's third cousin does. Can they hook you up? Sorta. Most employees get a certain number of guest passes (or "buddy passes") per year that they can give to anyone they please. These are valid only on the employee's airline, and they're usually ID90's. Remember, that's 90% off the full walkup fare, so it can still involve significant cost. Most employees are reluctant to give these to anyone they don't know very well just because if the guest makes a nuisaince of themselves, the employee will hear about it. So if you are given a buddy pass, be on your best behavior.

Ah yes, the wonderful world of non-rev travel. It's one of the biggest perks of working for an airline, and indeed is the only reason many people continue to work in the airlines. Most people outside the airline world aren't familiar with how it works, though.

"Non-rev" is short for non-revenue passenger, but is also used as a verb to describe traveling as a non-rev, i.e. "I'm non-reving to Sydney next week." Non-revs are typically airline employees, parents, spouses, children, and guests. Airline employees traveling on company business aren't considered non-rev, since they are guaranteed a seat. Non-revs travel standby, so they only fly if there's a seat left for them. Once all regular passengers, employees on company business, and revenue standby passengers have boarded, any remaining seats are given to non-revs according to a pre-determined "priority list." A priority list might look like this:

- Employee, parents, spouse, child: According to employee's date of hire.

- Non-revs from closely related airlines, ie United Express employee on United.

- Persons traveling on an employee's guest pass.

- Employees (and parents, spouse, children) from other airlines with pass agreement - priority determined by check-in time.

Traveling solely on one's own airline or even close codeshares would be pretty limiting, so most of the world's airlines have worked out pass agreements with each other. We purchase non-rev tickets on these airlines through our own airline's ticket counters. The cost varies with each pass agreement. Many tickets, like on United, are "ID90." This means that you pay 10% of the full walkup fare, which can get pretty expensive. You can often find deals on Expedia or Hotwire that are cheaper than ID90s - for a ticket that's positive space! A number of carriers have a flat service charge, which is usually $30-50 (plus tax) for domestic roundtrip travel, around $60-80 for Hawaii or Mexico, and $120-200 for Europe or Asia. Another type of pass that's becoming increasingly popular, especially with foreign carriers, is ZED (Zonal Employee Discount). The cost of a ZED pass depends on the distance traveled, and is the same price for all airlines that accept it. For example, a segment of 4080-5000 miles costs $60 plus tax. It's much cheaper than ID90's and most service charges, and once fully implemented it'll be much more flexible, since passes will be interchangeable among carriers.

Of course, the tax man will always take his due. When buying non-rev tickets on other airlines, you'll have sales tax, airport use fees, and security fees added on. For international travel, most countries add an exorbitant departure tax - $40-80 is common. You pay this even on your own airline, which usually takes it out of your paycheck.

After purchasing the ticket, you need to research which flights to take. I regularly download current timetables for about 30 airlines on my computer; many employees keep them on their PalmPilots or Blackberries. When direct flights aren't feasible, I'll try to connect through the hub city with the most options. For example, if I was trying to get from Portland to Cleveland, I'd probably connect through Chicago, because then I'd have AA, AS, and UA to Chicago, and AA, UA, and DL to Cleveland. Early morning flights sometimes have lighter loads, but afternoon flights may have seats opened up by misconnecting passengers. Eastbound redeye flights used to be a good option for non-revs but have become very popular the last few years. Fridays and Sundays are very bad days to travel standby; Tuesday and Wednesday are best.

Your next step is to see what the load factors look like. On your own airline or a close codeshare, the company often provides a phone number or website where you can check loads. If it's another carrier, a friend at that airline can be a great resource to check loads for you. No friends? Call the airline's reservations line and identify yourself as a non-rev. Some res agents will give you the exact loads, while others will play coy ("it looks okay." What's that mean!?). It's best to check a day or two before the flight at the soonest. If it's seriously oversold, find something else. If there are a few seats left or it's only slightly oversold, you can still try for it, but come up with a good backup plan or two. If 10% or more of the plane is open, you should be fine unless cancellations screw up your plan.

Before showing up at the airport, you need to list yourself, ie get yourself in the airline's reservation system. At your own airline there's probably a website and/or phone number for this; at other airlines you'll do it through their reservation hotline. Once at the airport, you'll go to the check-in counter or kiosk to check in like a regular passenger. You'll get a pass to get through security. At the gate, the agents will assign remaining seats to non-revs towards the end of the boarding process. Just wait for your name to be called. Be ready to go as soon as it is, or they'll give your seat away to the next non-rev on the priority list.

Whether traveling on your own airline or another, there is a code of conduct for non-revs to follow. First, you're expected to dress up. No sandles, no halter tops, no holey jeans or t-shirts, no sweatpants, no ratty sneakers, certainly no pajamas. In other words, don't dress like 50% of today's passengers. If you want any chance at first class, business casual is a minimum. Secondly, don't be a jerk to the gate agents, even if they're rude to you. Be polite and undemanding, and don't ask about open seats every three minutes. If you don't get on, don't protest. If you do get on, introduce yourself as a non-rev to the flight attendants and let them know where you're sitting if they need your help. Don't consider yourself home free until the cabin door is closed and the plane is pushing back; I've had gate agents run onboard at the last minute to replace me with a paying passenger. When the flight attendants offer you a meal, make sure there's enough for everybody first. And when the flight is over, help the flight attendants clean up if that's one of their duties (ie Southwest, jetBlue, most regional airlines, etc).

These days, the U.S. airlines are flying around with some very full airplanes; how they continue to lose massive amounts of money is beyond me. It makes it pretty tough to be a non-rev. The key is staying flexible. Accept that you're not going to get on all the flights, and have a good backup plan. Buy plenty of backup passes on other airlines; they're all refundable if you don't use them. Leave plenty of time in your plans for travel, and don't be surprised if you spend some significant time waiting in airline terminals. I've even spent the night in a few airports. Usually, though, by monitoring the loads, traveling at non-peak times, and making good backup plans, you can get around with a minimum of fuss.

So you don't work for the airlines, but your sister's friend's third cousin does. Can they hook you up? Sorta. Most employees get a certain number of guest passes (or "buddy passes") per year that they can give to anyone they please. These are valid only on the employee's airline, and they're usually ID90's. Remember, that's 90% off the full walkup fare, so it can still involve significant cost. Most employees are reluctant to give these to anyone they don't know very well just because if the guest makes a nuisaince of themselves, the employee will hear about it. So if you are given a buddy pass, be on your best behavior.

Wednesday, March 01, 2006

Rock & A Hard Place

I just got back from a four day trip that had quite a few legs in and out of Sun Valley, the first time I've been back since my unexpected Boise diversion. The poor weather across most of the west coast - strong wind, turbulence, low clouds, rain and snow - guaranteed some headaches for the Sun Valley turns.

When the Sun Valley airport is unusable, we operate out of Twin Falls, located about 90 minutes south. The company has a pretty good procedure to ensure that the flights stay on time when this happens. Outbound passengers call a hotline several hours before departure; if Sun Valley is closed, they are instructed to show up at the terminal some time before the scheduled departure time to ride to Twin Falls on the chartered coach. Ideally, the bus arrives in Twin Falls before the airplane does; the inbound passengers ride back to Sun Valley on the same bus. The decision to operate out of Twin Falls or not is made several hours prior to the arrival time.

On Monday we flew out of TWF twice, going to and coming from Oakland. The weather was getting worse the whole day, so I didn't hold out much hope for making it into Sun Valley on our two turns there on Tuesday. Indeed, as we prepared to depart for SUN on Tuesday morning, the weather began to deteriorate again. Still, it was a little late for the company to switch operations to Twin Falls. We decided to give it a shot.

Approaching Sun Valley, the ATIS was calling the weather a 1700' broken ceiling and 3 miles' visibility in light rain. This posed two problems. First, that's right at the minimums for the RNAV (GPS) W Rwy 31 approach. Secondly, even if we got in, we couldn't depart IFR. Take a look at the takeoff minimums here (the airport is listed under Hailey, ID). Takeoff minimums for runway 13 include a 2700' ceiling. Unlike general aviation, the airlines must comply with takeoff minimums. We called our dispatcher and informed him of the problem; he suggested that we attempt an approach, and if we got in the weather was good enough to depart VFR. We told him we'd try the approach but gave him no guarantees on being able to depart.

The approach was as tight as I've had in Sun Valley without going missed. We broke out right at minimums and were just able to see the runway. The ride in was pretty bumpy thanks to a 40 knot wind over the nearby ridges, but we got down safely. Next step: figure out how to get back out.

At most airports, the IFR takeoff minimums are far below the minimums for visual flight, so being below takeoff minimums means you're not going anywhere. At places like Sun Valley where the departure minimums are very high, you have another few options: departing VFR, or departing IFR with a restriction to maintain VMC (visual conditions) until a certain point. We do this very seldom at the airlines, so it sent the captain and I scurrying for our Flight Operations Manuals (FOMs).

To go VFR or depart with a VMC restriction, we would need at least three miles visibility and a 1000' ceiling; by this time the airport was at 5 miles & 1900'. So far, so good. We would need to maintain VFR cloud clearances (500' below clouds) and stay at least 500' above any terrain. No problem. Our FOM contains an additional restriction on VFR departures: it can only be used from an airport lacking an ATC facility. KSUN has a tower, so that wouldn't work. Our only chance to get out was to depart IFR with a VMC climb restriction.

Here's the catch: With a VMC climb restriction, you must be able to maintain visual conditions all the way to the minimum altitude for IFR in your area, whether that be a minimum enroute altitude (MEA), minimum obstacle clearance altitude (MOCA), or minimum vectoring altitude (MVA). These can be quite high in mountainous areas. We got ground control to ask Salt Lake Center what the minimum altitude was near Hailey NDB, just outside the valley, and it turned out to be 9000'. With the ceiling at 7200', we could maintain VMC up to 6700 feet but then would have no way to legally climb to 9000. We couldn't legally depart - we were stuck.

Well, not quite. While we were burrowing into the FOM, the weather was improving, so by the time we were ready to call our dispatcher and tell him no-go, the ATIS had been updated and it was now officially 10 miles vis, broken ceiling at 3200. Now the airport was above takeoff minimums so we could depart as usual, using the published departure procedure.

These are the kinds of sticky situations that most airline crews encounter pretty infrequently. Most of us are pretty unfamiliar with the rules that apply to these situations, which is why we carry the FOM with us and refer to it as needed. Of course, just because the rulebook says you can do it doesn't always mean you should do it, and that's where experience and judgement have no substitute.